To the Editor,

The use of cryopreserved homografts as complete aortic root replacements was introduced for the first time over 3 decades ago with considerable advantages with respect to biological heart valves such as greater durability, lower risk of endocarditis, and better hemodynamic profile with a much greater preservation of the ventricular function in the long run.1 However, most of these grafts start degenerating 10 years after being implanted, and they often present with massive calcification of the homograft wall, and valvular dysfunction.2

In this context, surgical reintervention is associated with a very high risk given the need to operate on a heavily calcified aorta that often requires a new and total replacement of the aortic root,3,4 which is why transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) seems especially appealing. Homograft valves often degenerate presenting with clinically pure aortic regurgitation. Also, the aortic root often shows very extensive calcification at sinus and sinotubular junction level; paradoxically, however, annular calcification is sometimes a rare phenomenon.3,4 This can jeopardize the stability of the balloon-expandable valve. However, to this point, there is scarce scientific evidence on the role it plays in this specific anatomical context.

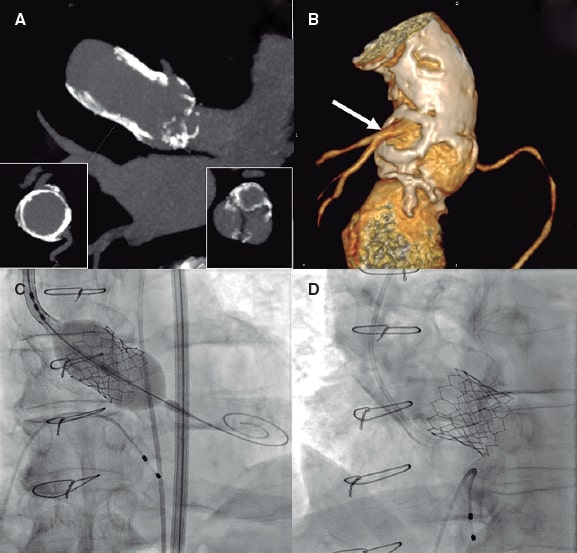

These are the cases of 5 consecutive patients (mean age: 68.4 ± 10.4 years) with degenerated aortic root homograft presenting with isolated aortic regurgitation (video 1 of the supplementary data) or double aortic lesion treated with transfemoral TAVI with a balloon-expandable valve between 2017 and 2021 in 1 center (table 1). A new surgical aortic valve replacement was discarded in all the cases because of the high risk associated with the procedure due to the massive and circumferential calcification of the homograft. Procedures were performed after obtaining the patients’ informed consent under deep sedation (patients #2, #3, and #4) or general anesthesia (patients #1, and #5, to improve tolerance to the transesophageal echocardiogram and achieve greater accuracy when placing the heart valve). Also, the procedures were transesophageal echocardiography-guided plus a computed tomography scan was performed prior to the procedure to assess the degree of calcification and the diameters of the graft. Direct implantation was performed with slow and prolonged inflation of the valve in all the cases except for patient #5 who underwent a first incomplete inflation followed by complete postdilatation (figure 1 and video 2 of the supplementary data) for showing significant resistance to the expansion during the initial inflation. In an female patient (patient #2 of table 1) a guidewire was advanced to protect the left main coronary artery during valve implantation (video 3 of the supplementary data).

Table 1. Patients with degenerated aortic homograft treated with transfemoral TAVI

| Patient #1 | Patient #2 | Patient #3 | Patient #4 | Patient #5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 84 | 70 | 63 | 69 | 56 |

| Sex | Woman | Woman | Woman | Man | Man |

| EuroSCORE II (%) | 23% | 7% | 4% | 10% | 5% |

| STS (%) | 17% | 5% | 3% | 7% | 3% |

| Indication for homograft | BAV-AAA | BAV-AAA | IE | IE | BAV-AAA |

| Age of homograft, years | 12 | 12 | 15 | 14 | 17 |

| Type of dysfunction | Severe AR | Severe AR | Double lesion | Severe AR | Double lesion |

| Transprosthetic pressure gradient (mmHg) | NA | NA | 80 | NA | 54 |

| Agatston score of the valve | 3824 | 1936 | 1873 | 1650 | 5555 |

| Agatston score of the homograft | 9100 | 9037 | 10 456 | 11 456 | 17 400 |

| Homograft calcification | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe |

| Diameter derived from the annulus (mm) | 24.8 | 24.2 | 23.2 | 25.7 | 28.02 |

| Perimeter of the annulus (mm) | 78 | 76 | 73 | 81 | 88 |

| Maximum diameter (mm) | 24 | 24 | 22 | 25 | 26 |

| Procedure | |||||

| Anesthesia | General | Sedation | Sedation | Sedation | General |

| Measure of the annulus (TEE, mm) | 25 | 25 | 22 | 24 | 24 |

| Edwards valve | SAPIEN XT 26 | SAPIEN 3 26 | SAPIEN 3 23 | SAPIEN 3 26 | SAPIEN 3 Ultra 26 |

| Access | Transfemoral | Transfemoral | Transfemoral | Transfemoral | Transfemoral |

| Paravalvular regurgitation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pacemaker | No | No | No | No | No |

| X-ray image time (min) | 19 | 23 | 36 | 29 | 21 |

| Contrast (mL) | 60 | 100 | 80 | 60 | 60 |

| Complications according to the VARC-3 | No | No | No | No | No |

| Follow-up | |||||

| Follow-up time (months) | 41 | 35 | 14 | 10 | 1 |

| Death after 1 year | None | None | None | None | NA |

| Heart failure after 1 year | None | None | None | None | NA |

| Stroke after 1 year | None | None | None | None | NA |

| Pacemaker after 1 year | None | None | None | None | NA |

| Transaortic gradient (mmHg) | 24 | 15 | 35 | 20 | NA |

| Aortic regurgitation | No | No | No | No | NA |

| Events at the follow-up | None | None | None | None | NA |

|

AAA, ascending aortic aneurysm; AR, aortic regurgitation; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; IE, infectious endocarditis; NA, not applicable; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; VARC-3: Valvular Academic Research Consortium-3. |

|||||

Figure 1. A: multiplanar reconstructed computed tomography images showing the calcified homograft (cross-sectional view in the left lower quadrant) with less calcification in the aortic valve (cross-sectional view in the right lower quadrant. B: 3D reconstruction of the aortic root through computed tomography scan with posterior view showing severe calcification of the homograft that preserves the left main coronary artery neo-ostium (arrow). C: implantation of a SAPIEN 3 Ultra 26 mm aortic valve (Edwards Lifesciences, United States) with incomplete expansion that is completed in a second inflation. D: final angiographic image showing severe calcification of the homograft with a properly expanded valve.

Implantation was successful in all the patients, and nobody showed significant paravalvular aortic regurgitation or atrioventricular block after the procedure. Only 1 complication was reported: the presence of a contralateral femoral artery pseudoaneurysm that was treated with ultrasound-guided compression (patient #3 of table 1). The mean hospital stay was 5.2 days. After a median follow-up of 20.2 ± 15.2 months all patients remained free of events, and all the valves were working properly.

To this date, most of the experienced published on degenerated aortic homografts treated percutaneously has been limited to the use of self-expanding valves5,6 possibly for their capacity to be retrieved and repositioned given the fear of valve embolization due to the lack of calcium in the valve annulus. However, the use of balloon-expandable valves can also bring additional advantages: a) it guarantees the proper expansion of the valve, b) there is less interference of metal material in the calcified homograft wall, and c) it preserves access to coronary arteries at the follow-up of patients whose mean age is often lower compared to that of most patients treated with TAVI.

Degenerated aortic root homograft is a complex scenario on which there is scarce scientific evidence available. Our series of homografts treated with balloon-expandable valve shows that it is a feasible and safe option for this type of patients.

FUNDING

None reported.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed to the preparation, writing, and review this letter.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None whatsoever.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Vídeo 1. Unzuéa L. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M21000254

Vídeo 2. Unzuéa L. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M21000254

Vídeo 3. Unzuéa L. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M21000254

REFERENCES

1. González-Pinto A, Vázquez RJ, Sánchez A, et al. Homoinjerto de raíz aórtica para el tratamiento quirúrgico de las afecciones de la válvula aórtica con aorta ascendente dilatada. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2004;57:412-416.

2. Amabile N, Bical OM, Azmoun A, Ramadan R. Nottin R, Deleuze PH. Long-term results of freestyle stentless bioprosthesis in the aortic position:a single- center prospective cohort of 500 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1903-1911.

3. Sadowski J, Kapelak B, Bartus K, et al. Reoperation after fresh homograft replacement:23 years'experience with 655 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:996-1000.

4. Joudinaud TM, Baron F, Raffoul R, et al. Redo aortic root surgery for failure of an aortic homograft is a major technical challenge. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:989-994.

5. López-Otero D, Teles R, Goméz-Hospital JA, Balestrini CS, Romaguera R, Saiibi-Solano JF. Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica:seguridad y eficacia del tratamiento del homoinjerto aórtico disfuncionante. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65:350-355.

6. Chan PH, Di Mario C, Davies SW, Kelleher A, Trimlett R, Moat N. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in degenerate failing aortic homograft root replacements. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1729-1730.