To the Editor,

The current COVID-19 pandemic has changed our health system dramatically. The need to have resources available to assist the high volume of patients affected, the healthcare overload, and the need to limit exposure to the virus have led to the implementation of extraordinary measures like delaying the healthcare provided to patients with chronic conditions and the almost total suspension of elective procedures such as the transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).1

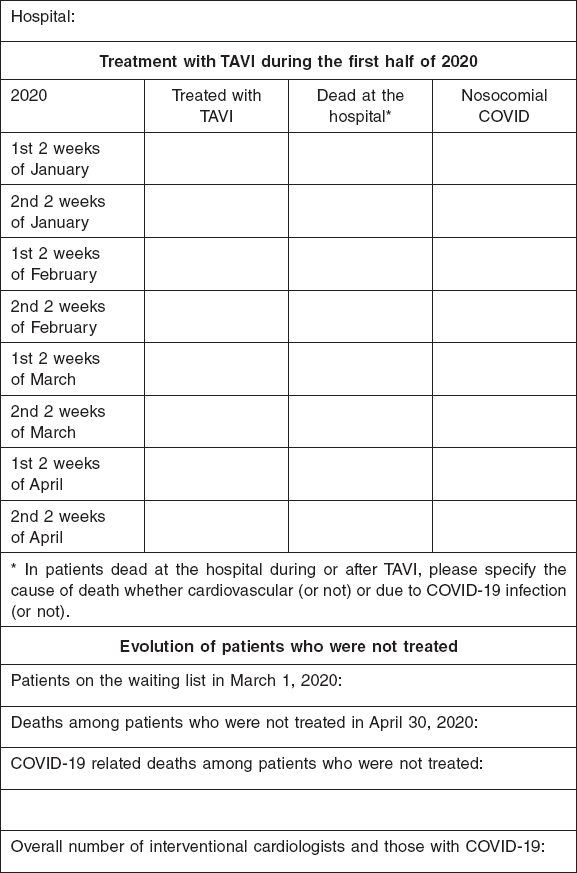

The Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) sent a survey to the hospitals included in the Spanish TAVI registry with the following objectives: quantify the temporal damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to TAVI procedures in our country, analyze the disease progression of patients not treated because of the pandemic, study the rate and consequences of the infection in patients treated during this period of time, and ultimately assess the number of COVID-19 infections within the medical staff of the cath labs. Forty out of the 46 centers included in the national registry participated in the study (86.9%). The parameters of thid survey are shown on figure 1.

Figure 1. Survey sent to the participating centers.

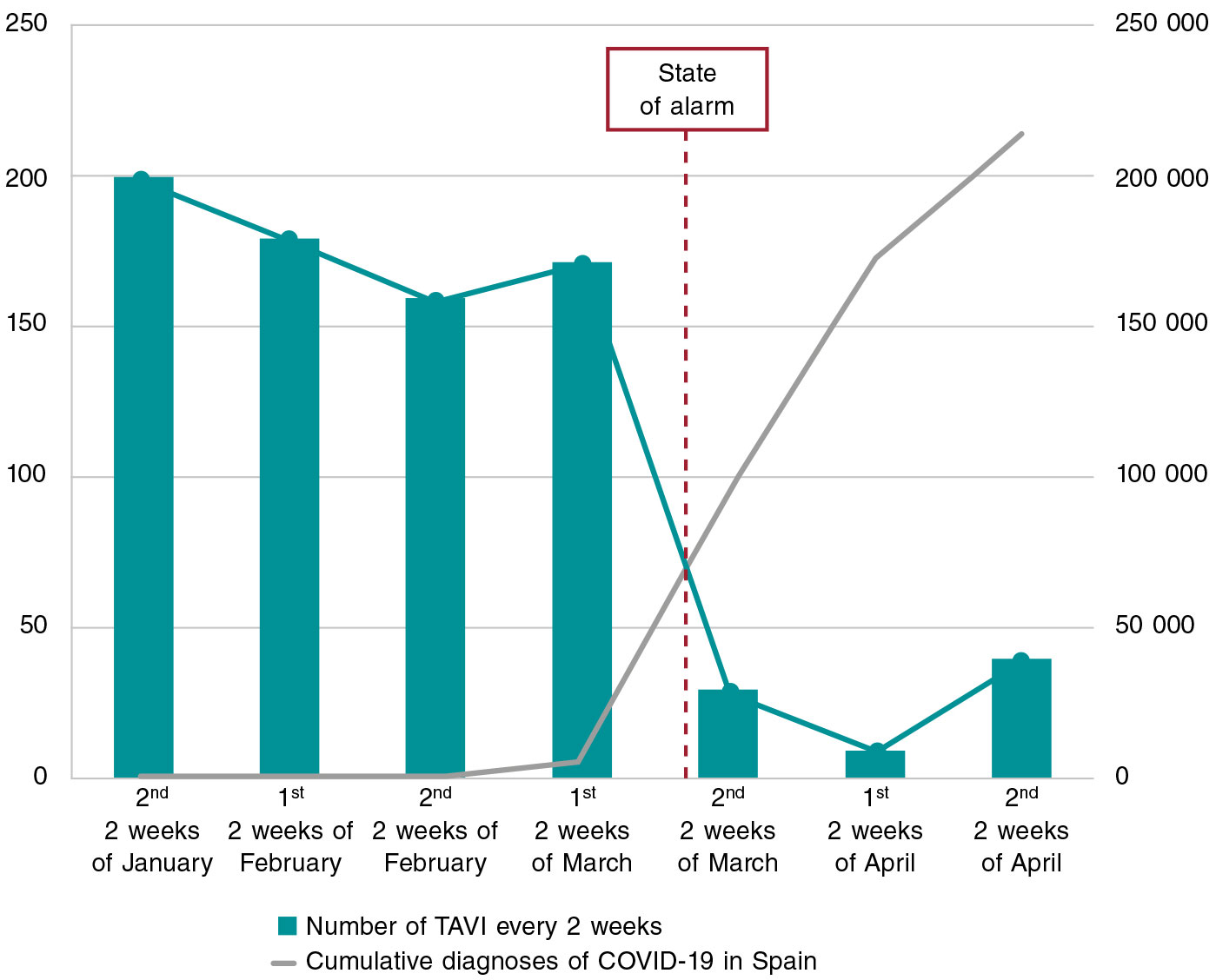

From January 1 to April 30, 2020, 890 TAVIs were performed. Most of them (813 out of the 890, 91.4%) until the first 2 weeks of March, and only 77 (8.6%) since the state of alarm was declared, which is a 95% drop in the activity developed. If we take 2 comparable time periods before and after the declaration of the state of alarm—the month of February and the first 2 weeks of March 2020 vs the second 2 weeks of March and the month of April—the drop is still very significant: 509 TAVIs vs 77 TAVIs (an 86.9% drop) (figure 2). After TAVI, 18 patients (2.0%) died at the hospital, most of them of cardiovascular causes (16/18, 88.9%). During admission, 7 patients (0.8%) contracted the virus, all of them between the months of February and March, and most of these infections occurred before the declaration of the state of alarm (6 vs 7; 85.7%). Two of these patients died. Therefore, in February and within the first 2 weeks of March, the rate of nosocomial COVID-19 was 1.2%, lethality was 33.3%, and mortality rate due to nosocomial COVID-19 was 0.4%. During the state of alarm, only 1 of these 77 patients treated with TAVI had nosocomial COVID-19. This patient ended up dying (rate of nosocomial COVID-19 and mortality rate due to nosocomial COVID-19 of 1.3%). There are data available of the waiting lists of 37 of the 40 participating centers. Back in March 1, 2020, 810 patients were waiting to receive their implants. Twenty-four (2.9%) patients died while on the waiting list within the following 2 months (until April 30). Most deaths (20 out of the 24; 83.3%) were due to aortic valve disease and 4 (16.7%) to COVID-19 infection. Another 4 patients (0.5%) required an emergency TAVI, had no complications, and a favorable progression after the procedure. Therefore, 28 patients (3.5%) died while on the waiting list or required an emergency TAVI. Finally, 15 (6.9%) out of the 217 interventional cardiologists from the cath labs of the participating centers tested positive for COVID-19 in the polymerase chain reaction tests performed.

Figure 2. Temporal evolution of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in relation to the incidence of COVID-19 in Spain.

The national registry shows a significant reduction in the number of percutaneous coronary interventions performed to treat aortic valve disease since the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in our country. The risk of nosocomial infection and healthcare overload added to the risk associated with postponing these procedures2,3 make it necessary to keep a follow-up and individualized assessment of every patient to be able to prioritize the indications.4 A practical consequence of these data is that the patients’ mortality rate while on the waiting list was clearly higher (3%) compared to the mortality rate due to nosocomial COVID-19 (1.3%). This may lead to the need of having to keep TAVI programs if logistically possible in future pandemics we may encounter. Finally, it is essential to guarantee the adequate protection of patients to avoid nosocomial infections that may be life-threatening and provide individual protection equipment (IPE) to the healthcare professionals who may be exposed to infections.5

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript. R. Moreno is associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed.

Annex. Participanting hospitals and principal investigator in each center

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago: Ramiro Trillo-Nouche |

| Complejo Universitario de Vigo: José Antonio Baz |

| Hospital Universitario San Carlos: Pilar Jiménez-Quevedo |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía: Manuel Pan |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca: Eduardo Pinar |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge: Rafael Romaguera |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria: José María Hernández |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves: Eduardo Molina |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron: Viçens Serra |

| Hospital Universitario La Fe: Francisco Ten |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias: Raquel del Valle |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid: Ignacio Amat |

| Hospital Ramón y Cajal: Luisa Salido |

| Hospital Clínic Barcelona: Ander Regueiro |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón: Enrique Gutiérrez |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau: Dabitz Arzamendi |

| Hospital General Universitario de Alicante: Vicente Mainar |

| Hospital La Paz: Raúl Moreno |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr Negrín: Pedro Martín |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla: José M. de la Torre-Hernández |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío: Manuel Villa |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol de Badalona: Eduard Fernández-Nofrerias |

| H. Puerta del Mar: Livia Gheorge |

| Hospital Universitario de León: Carlos Cuellas Ramón |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia: Sergio García-Blas |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet: María Cruz Ferrer |

| Hospital Universitario de Cruces: Roberto Blanco Mata |

| Hospital Universitario Regional de Málaga: Cristóbal Urbano |

| Hospital de Basurto: Leire Andraka |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra: Valeriano Ruiz Quevedo |

| Hospital Universitario de Badajoz: Juan Manuel Nogales |

| Hospital Universitario de Salamanca: Ignacio Cruz |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo: José Moreu |

| Hospital Universitario de La Princesa: Fernando Alfonso |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda: Juan Francisco Oteo |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz: Antonio Piñero |

| Hospital Universitari Son Espases: Vicente Peral |

| Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez: Jessica Roa |

| Hospital General de Valencia: Alberto Berenguer |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra: Miguel Artaiz |

| Hospital General de Valencia: Alberto Berenguer |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra: Miguel Artaiz |

REFERENCES

1. Romaguera R, Cruz-González I, Jurado-Román A, et al. Considerations on the invasive management of ischemic and structural heart disease during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak. Consensus statement of the Interventional Cardiology Association and the Ischemic Heart Disease and Acute Cardiac Care Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:106-111.

2. Chung CJ, Nazif TM, Wolbinski M, et al. Restructuring Structural Heart Disease Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic:JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2974-2983

3. Shah PB, Welt FGP, Mahmud E, et al. Triage Considerations for Patients Referred for Structural Heart Disease Intervention During the COVID-19 Pandemic:An ACC/SCAI Position Statement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1484-1488.

4. Moreno R, Ojeda S, Romaguera R, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Cruz-González I. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Recommendations from the ACI-SEC. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M20000137

5. Romaguera R, Cruz-González I, Ojeda S, et al. Gestión de las salas de procedimientos invasivos cardiológicos durante el brote de coronavirus COVID-19. Documento de consenso de la Asociación de Cardiología Intervencionista y la Asociación del Ritmo Cardiaco de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:106-111.

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Avda. Menéndez Pidal s/n, 14004 Córdoba, Spain.

E-mail address: (S. Ojeda).