Before speculating on where interventional cardiology is heading to, it may be helpful to reflect on its true origin. For many of you, early or halfway through your career, interventional cardiology may seem a well-established and mature subspecialty. For you it has always been a major component within the field of cardiology. However, for those of us who were already here before interventional cardiology even existed and have witnessed its birth, child- hood, and adolescence, interventional cardiology is just a moment in time. Currently, we feel pretty confident that we are treating coronary artery disease adequately with prompt interventions for the management of acute myocardial infarctions and chronic conditions with sophisticated instruments, excellent results, and satisfied patients. We also felt confident when we had balloons only. Yes, there were many failures back then, but interventional cardiology would have never flourished if it was not for optimism. I keep a video recording of our colleague and father of interventional cardiology, Andreas Gruentzig, MD, just before his untimely death. He said that balloons were the solution for many conditions, but also that we needed much more than that if we wanted to solve the obvious problems of coronary artery obstruction. The next decade would witness innovation attempts, some of them ranging from excellence to eccentricity1 All types of lasers to burn, seal, selectively ablate only abnormal tissue; hot-tip catheters; cold freezing instruments; cutters and scrapers; and finally scaffolds that we would call stents. Peripheral artery interventions followed a similar path. Although these came before coronary interventions, these techniques evolved slower. The ability to perform minimally invasive procedures for structural heart disease lagged behind. In the late 1980s, Alain Cribier, MD presented the idea of balloon dilatation of the aortic valve at our Emory courses2 We tried it for some time. Fifteen years later he implanted the first transcatheter aortic valve. It takes a while before ideas come to life. Back in 1990, we predicted that restenosis would be conquered by a device to hold the artery open combined with locally-delivered anti-proliferative agents. At first, we tried radiation, but cell-cycle inhibition stents eventually became the standard of care.

There were many difficulties then. Some were overcome, and some carried their own issues. What are the problems we face today, and how will they be approached in the future? The most successful coronary intervention occurs in the setting of acute myocardial infarctions. Making this technology widely available is still challenging because even though it can be done, myocardial salvage has not been completely solved. Innovations such as left ventricular support combined with reperfusion while paying special attention to microcirculation and its response to reperfusion deserve further research. We still do not know what to do with non-culprit but narrowed coronary arteries in the setting of myocardial infarctions.

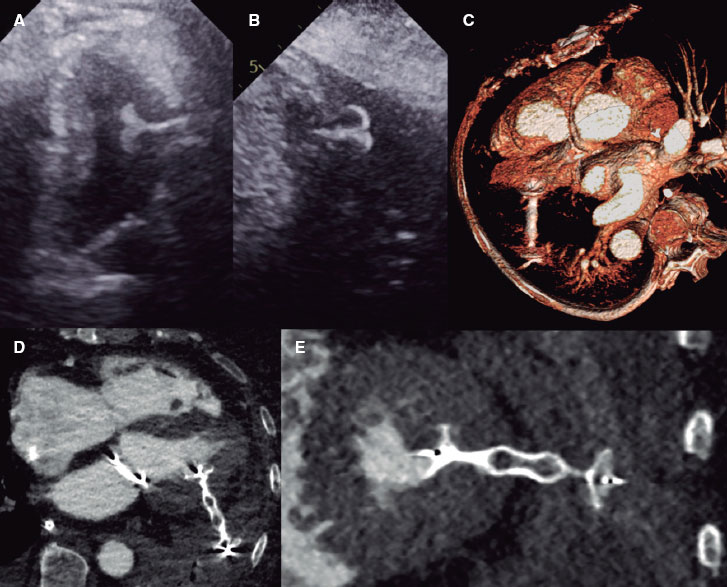

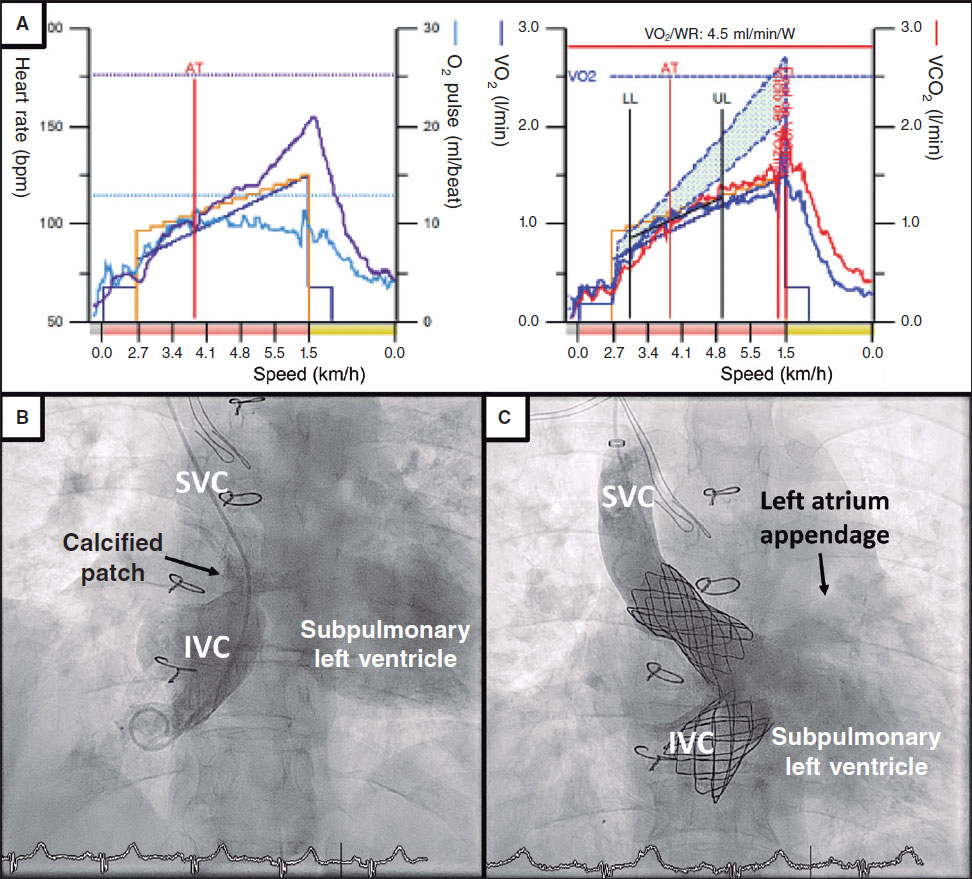

Techniques for opening chronic total occlusions and bifurcation lesions have progressed, but we still don’t have dedicated devices for bifurcations, and reopening chronic total occlusions through the true lumen requires innovations that are still to come. Although percutaneous aortic valve implantation has evolved faster than any of us would have anticipated, long-term results are still awaited, and mitral and tricuspid valve replacements are still in their infancy. Peripheral endovascular therapies seem spectacular, but endo-leaks and aneurysm expansion have not been completely solved yet.

Also, the lines between disciplines are blurry. Stroke intervention is the most dramatic advance in the field. Will clot retrieval from cerebral arteries remain the scope of neurologists only? There are not enough of them, and cardiologists are entering their specialty. On the other hand, interventional cardiology will not be the sole domain of cardiologists. A recent approach to the excessive stroke rate from carotid stenting has resulted in the direct surgical exposure of the artery with stent implantation combined with reverse carotid blood flow enabled by a shunt via the femoral vein. This kind of innovations combine surgical skills and training together with catheter skills. An interdisciplinary collaboration that can be perfected in some healthcare systems. A trial sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is now underway to assess the validity of a hybrid approach for the management of coronary revascularization, ie left internal mammary artery to the left anterior descending artery through minimally invasive techniques combined with drug-eluting stents for the management of other lesions.3

The problem of cardiovascular disease will not be solved with devices alone. Recognizing the progression of atherosclerosis not only in non-stented segments but also inside the stents will turn interventional cardiologists into preventive cardiologists. The dramatic breakthroughs in the management of lipids and the cardiovascular effects of new drugs for the management of diabetes means that interventional cardiologists must be competent in these fields as well, since these therapies may become the most relevant “devices” in the future. A total paradigm shift may be underway in the management of stable ischemic heart disease. Diagnosis is now moving away from ischemia detection only to non-invasive coronary imaging in the assessment of physiology and anatomy. Right now the U.S. is behind other countries when it comes to the implementation of CT angiography, but I predict it will become the diagnostic catheterization laboratory of the future. Ad hoc percutaneous coronary interventions during invasive catheterizations may have been acceptable so far, but now with the ability to define coronary obstructions and their physiological significance non-invasively, we can better plan medical therapy, percutaneous coronary interventions, or surgery. Unlike ad hoc percutaneous revascularizations during invasive catheterizations, this will allow true informed consents and facilitate proper diagnoses in patients who may not have agreed previously to an invasive diagnostic procedure.4

It will not reduce the number of interventions but it will certainly guarantee that only the correct ones are performed. A critical consideration for this subspecialty is what the training should look like in this rapidly changing field. Not everyone will be an expert in every aspect, which is why training and continuing medical education will create the expertise required.

The future is always unpredictabe but if the past teaches us anything is that the field of interventional cardiology has a challenging and rewarding future. It is a new field of expertise where there is still much to be done. The launch of this new journal will give you the opportunity to disseminate new knowledge that will shape the future. As my term as editor of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions was coming to an end I wrote an editorial that was published both in our journal and EuroIntervention5 I called it “The golden age of publishing in interventional cardiology”. Well, that age has not passed yet. I believe that the ability to publish good papers in quality journals has stimulated young investigators to do what needs to be done. This journal will be unique because it will be published in both English and Spanish. I hope that those who feel more comfortable using Spanish will be stimulated not only to read about the advances made on interventional cardiology, but also to contribute to its progress with more publications of their own research. This journal should be popular not only in Spain but throughout the Spanish-speaking countries in the Americas. Congratulations and best wishes to the editors of REC: Interventional Cardiology for this important contribution to our field.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Baim DS, Kent KM, King SB III, et al. Evaluating new devices. Acute (in-hospital) results from the new approaches to coronary intervention registry. Circulation. 1994;89:471-481.

2. Cribier A, Savin T, Saoudi N, et al. Percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty of acquired aortic stenosis in elderly patients:an alternative to valve replacement?Lancet. 1986;1:63-67.

3. Kayatta MO, Halkos ME, Puskas JD. Hybrid coronary revascularization for the treatment of multivessel coronary artery disease. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7:500–505.

4. Collet C, Onuma Y, Andreini, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography for heart team decision-making in multivessel coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3689–3698.

5. King SB III. Editor's Page:Interventional Cardiology's Golden Age of Publishing. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2017;10:1186-1187.

Corresponding author: Emory St Joseph’s Hospital, 5665 Peachtree Dunwoody Rd, NE, Atlanta, GA 30342, United States.

E-mail address: spencer.king@emoryhealthcare.org (S.B. King III).