This is the case of a surgery performed on a 73-year-old man with severe aortic stenosis and severe coronary artery disease of both left anterior descending (LAD) and right coronary (RCA) arteries. Surgery included the implantation of a no. 21 St. Jude Trifecta aortic bioprosthesis (Saint Jude Inc, United States) and surgical coronary artery revascularization of left internal mammary artery to the LAD (LIMA-LAD) and saphenous vein to right coronary artery (SV-RCA). The patient presented with signs of progressive exertional angina pectoris exactly 1 month after surgery in an external consultation.

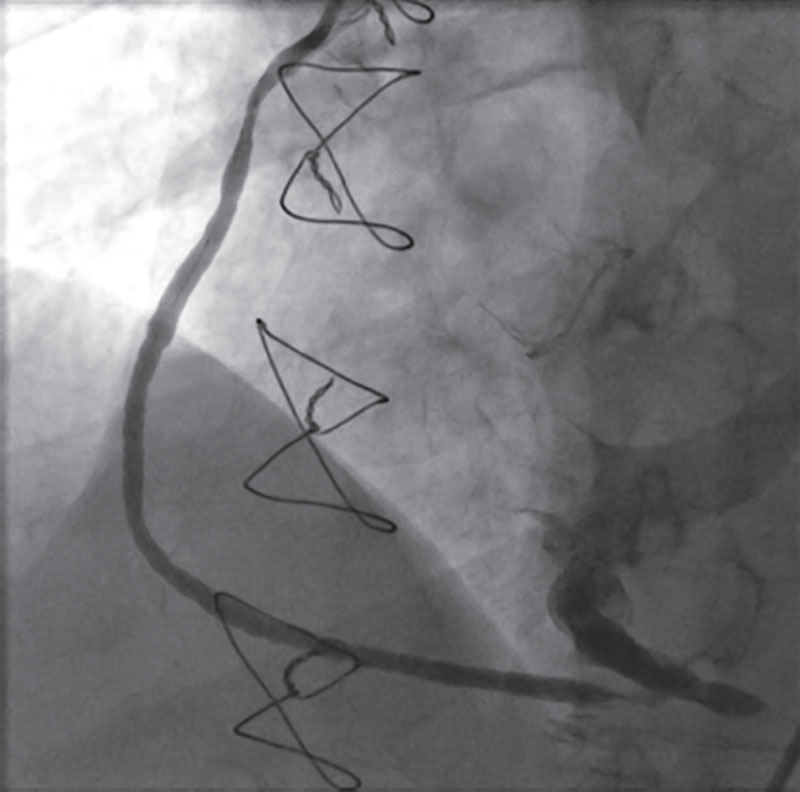

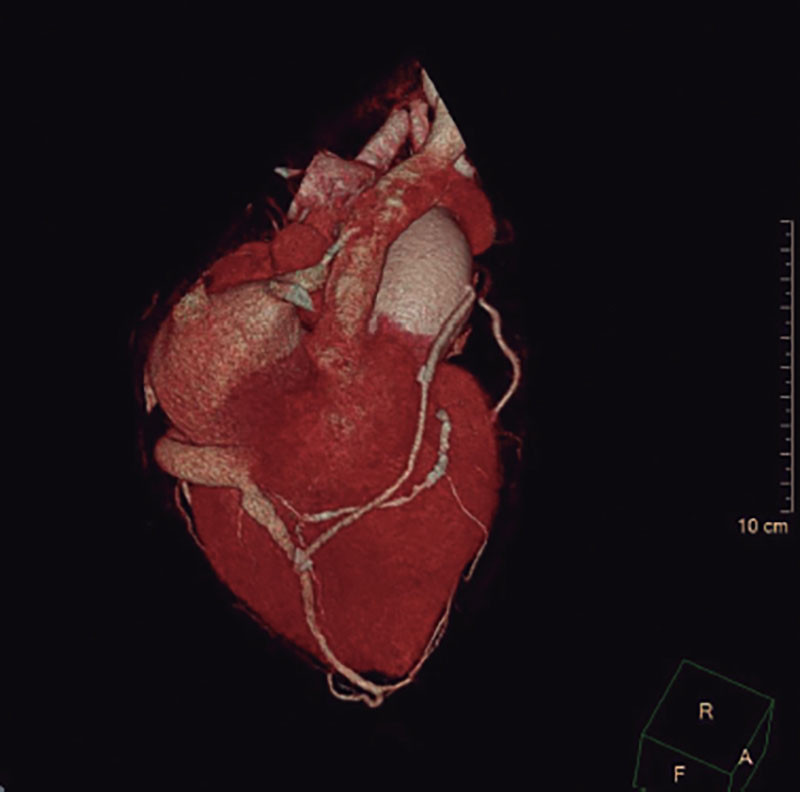

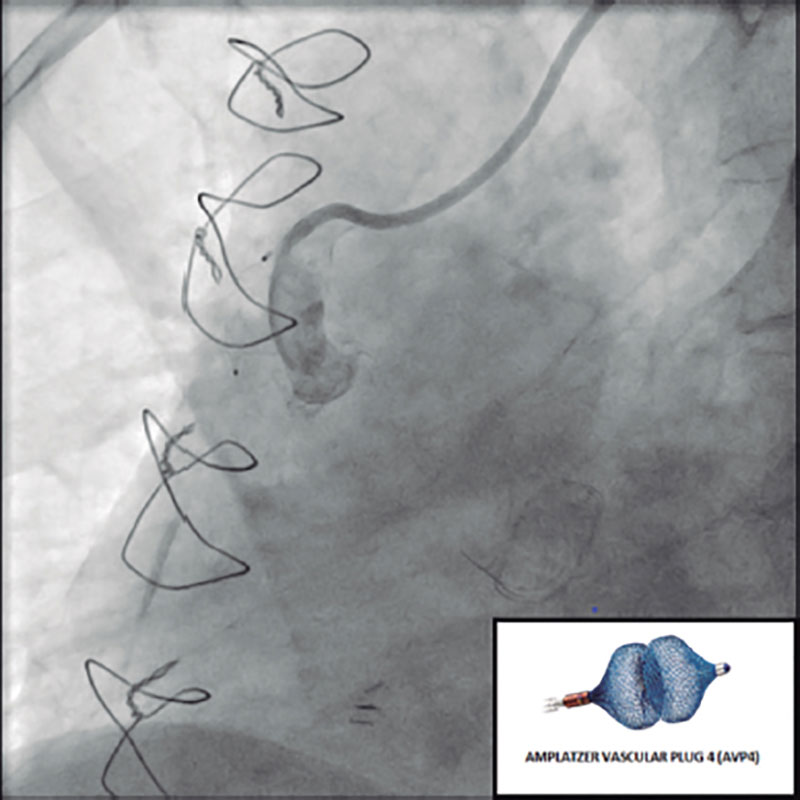

The transthoracic echocardiogram revealed the presence of a normally functioning aortic valvular bioprosthesis. The coronary angiography confirmed the already known native coronary artery disease, a patent LIMA-LAD grafting, and a SV grafting that remained unconnected to the distal RCA filling the coronary venous sinus (figure 1 and video 1 of the supplementary data). The cardiac computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the connection between the SV grafting and the middle cardiac vein that eventually drains into the coronary sinus (figure 2). The RCA was percutaneously revascularized by implanting 1 drug-eluting stent. In a medical-surgical session it was decided to close the SV grafting with the implantation of a 6 mm x 12 mm AVP4 (Abbot, United States) that turned out successful (figure 3 and video 2 of the supplementary data). The patient’s angina pectoris became alleviated after percutaneous revascularization and right chamber dilatation was prevented with the closure of the SV grafting.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

We should know the surgical coronary complications and bring alternative solutions to the table. This promotes collaboration between clinical cardiology, interventional cardiology, and cardiovascular surgery

All procedures were performed according to the ethical standards established by the institutional and national research ethics committee and in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki from 1964 and further amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study patient’s informed consent was obtained.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

R. Mori: data and figure curation, drafting of the original manuscript. D. Gemma: data and figure curation, drafting of the original manuscript. A. Casado: drafting of the original manuscript. F. Sliwinsky: drafting of the original manuscript. A. Romero: data and figure curation, drafting of the original manuscript. J. Palazuelos: idea, supervision, review, and edition.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None whatsoever.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Vídeo 1. Mori R. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000352

Vídeo 2. Mori R. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000352