To the Editor,

Very late stent thrombosis—the one occurring, at least, 1 year after stenting—is a rare complication of tremendous clinical relevance. The mechanisms underlying its physiopathology have been widely studied thanks to the use of intracoronary imaging modalities, especially optical coherence tomography. The 2 main mechanisms of action found are, in the first place, neoatherosclerosis, and secondly, no strut endothelization.1 Despite of this, its approach is still under discussion and focused on resolution or minimization of the factors leading to its appearance.

On the other hand, drug-coated balloon (DCB) has been part of the therapeutic armamentarium of interventional cardiologists for quite some time. Currently, its main indications are to treat in-stent restenosis, and small vessel de novo coronary artery lesions. New indications are emerging like bifurcations (especially of the side branch) and large vessel de novo lesions. However, there is a clinical setting where its use has instilled quite a few serious doubts: ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (STEACS). Since plaque rupture followed by thrombosis is its main pathogenic mechanism and it’s different from the therapeutic target of DCB—the inhibition of neointimal proliferation—the use of DCB to treat STEACS is ill-advised. Former studies on this matter have proven so.2 However, isolated, and well-designed studies have obtained good results like the REVELATION.3

However, in very late stent thrombosis—the one associated with the thrombotic phenomenon per se—other pathogenic processes are involved like restenotic lesions and neoatherosclerosis, which could respond to DCB therapy even with a lower risk of complications compared to new stenting since this approach is less aggressive and avoids stenting multiple overlapping stents in the culprit vessel.

This is the first series ever reported of patients with very late stent thrombosis treated with DCB. All of them signed the informed consent form, and received the approval of our hospital ethics committee.

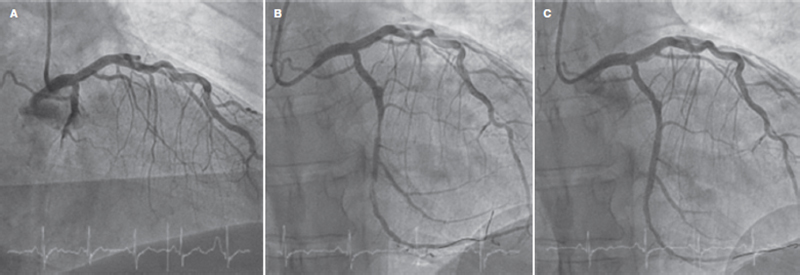

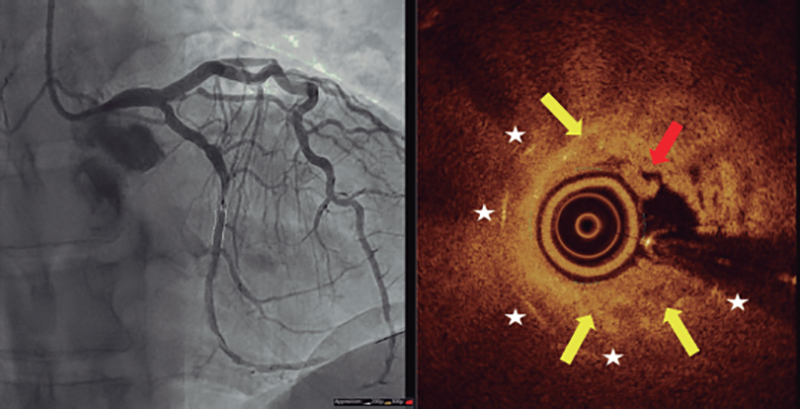

Table 1 shows the clinical, anatomical, and procedural characteristics of the 6 patients included. We should mention the very late onset of stent thrombosis that occurs in 1 of the cases occurred 19 years after the index procedure. A total of 4 patients had complete vessel thrombosis. In all of them percutaneous thrombectomy was performed unlike in the other 2 who had partial thrombosis with baseline TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) grade-3 flow. We should mention that in 2 out of the 6 patients significant changes were reportes regarding measurements taken on the days that preceded the onset of STEACS. In the first patient, single antiplatelet therapy was withdrawn due to a scheduled dental procedure while in the second patient, dual antiplatelet therapy was changed for single antiplatelet therapy plus oral antiacoagulation due to the presence of deep venous thrombosis. In the only patient treated with optical coherence tomography, neoatherosclerosis was identified as the pathogenic mechanism of thrombosis (figure 1 and figure 2). All the lesions received proper preparation with different predilatation and plaque modification devices before using the DCB, the SeQuent Please Neo with paclitaxel coating technology (BBraun, Germany) in all cases. No adverse events were ever reported at a median follow-up of 6 months.

Table 1. Clinical and procedural characteristics

| Patient #1 | Patient #2 | Patient #3 | Patient #4 | Patient #5 | Patient #6 | |

| Sex | Woman | Man | Man | Man | Man | Man |

| Age (years) | 71 | 81 | 83 | 52 | 63 | 75 |

| Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Diabetes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Dyslipidemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smoking | Yes | Former smoker | Former smoker | Yes | Former smoker | Former smoker |

| Kidney disease | No (Cr, 0.79) | No (Cr, 0.78) | No (Cr, 1.02) | No (Cr, 1.02) | No (Cr, 1.13) | No (Cr, 0.98) |

| Years since stenting | 19 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 10 |

| Previous treatment | ASA | NOA | ASA | ASA | Clopidogrel | NOA + clopidogrel |

| Location of culprit lesion | Mid-right coronary artery | Mid-left anterior descending coronary artery | Saphenous vein graft | Distal left circumflex artery | Diagonal branch | Mid-right coronary artery |

| Early TIMI grade flow | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Predilatation device | Scoring | NC | Cutting + NC | Scoring + cutting | NC | NC |

| Final TIMI grade flow | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Intracoronary images | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Size of DCB used | 3.5 | 2.5 + 3 | 4 | 3 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Treatment at discharge | ASA + prasugrel | NOA + ASA + clopidogrel | ASA + ticagrelor | ASA + ticagrelor | ASA + ticagrelor | NOA + ASA + clopidogrel |

| Follow-up (months) | 10 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Adverse events at follow-up | No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; Cr, plasma creatinine concentration (mg/dL); DCB, drug-coated balloon; NC, noncompliant balloon; NOA, new oral anticoagulant; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

||||||

Figure 1. Angiography of the patient treated with optical coherence tomography. Baseline coronary angiography imaging showing a thrombotic occlusion at left circumflex artery level (A) after predilatation with plaque modification balloons (B), and final clinical outcomes after drug-coated balloon implantation (C).

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography imaging with angiographic co-registration after achieving flow. Yellow arrows are indicative of the process of neoatherosclerosis (restenotic heterogeneous plaque), the red arrow points at a red thrombus, and white stars are indicative of the stent struts.

Scientific evidence on the utility of DCB to treat STEACS due to very late stent thrombosis is scarce, only just a few isolated case reports.4 Since, conceptually, the DCB looks like an excellent therapeutic tool in this clinical setting, we believe trials with big enough samples and clinical and angiographic follow-up should be conducted to confirm or refute such hypothesis. We should mention the need for proper lesion preparation before using DCBs, and how important—actually mandatory—should be to use intracoronary imaging modalities (especially optical coherence tomography for its greater resolution capabilities) to clearly identify the pathogenic mechanisms involved. Therefore, the scarce use of such techniques in our series was our study main limitation.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors were involved in the process of patient recruitment and manuscript revision. J. Valencia drafted the manuscript, conducted the clinical follow-up, and prepared the images.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Adriaenssens T, Joner M, Godschalck TC, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Patients With Coronary Stent Thrombosis. A Report of the PRESTIGE Consortium (Prevention of Late Stent Thrombosis by an Interdisciplinary Global European Effort). Circulation. 2017;136:1027-1031.

2. Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan-Ahmad WA, et al. Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary Artery Disease: Third Report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1391-1402.

3. Vos NS, Fagel ND, Amoroso G, et al. Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Versus Drug-Eluting Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction: The REVELATION Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1691-1699.

4. Alfonso F, Bastante T, Cuesta J, Benedicto A, Rivero F. Drug-Coated Balloon Treatment of Very Late Stent Thrombosis Due to Complicated Neoatherosclerosis. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106:541-543.