ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: This study primary endpoint was to present the in-hospital all-cause mortality of the Spanish TAVI registry from its inception until 2018. Secondary endpoints included other in-hospital clinical events, 30-day all-cause mortality, and an assessment of the time trend of this registry.

Methods: All consecutive patients included in the Spanish TAVI registry were analyzed. In this time-based analysis, the population was been divided into patients treated before 2014 (cohort A: 2009-2013) and patients treated between 2014 and 2018 (cohort B).

Results: From August 2007 to June 2018, 7180 patients were included. The mean age was 81.2 ± 6.5 years and 53% were women. The logistic EuroSCORE was 12% (8-20). Transfemoral access was used in 89%. In-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality was 4.7% and 5.7%, respectively. On the time-based analyses during the hospital stay, the rate of myocardial infarction, stroke, need for pacemakers, tamponade, coronary obstruction, and vascular complications was similar between both groups. However, cohort B showed less need for conversion to surgery and malapposition of the valve. Also, the implant success rate increased from 93% to 96% (P< .001). In-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality was significantly lower in cohort B, ([OR, 0.65; IC95%, 0.48-0.86; P= .003] and [OR, 0.71; IC95%, 0.54-0.92; P= .002], respectively).

Conclusions: The time trend analysis of the Spanish TAVI registry showed a change in the patients’ clinical profile and an improvement in the in-hospital clinical outcomes and 30-day all-cause mortality in patients treated more recently.

Keywords: Transcatheter Treatment of the Aortic Valve. Records. Severe Aortic Stenosis.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El objetivo primario de este estudio fue presentar la mortalidad total intrahospitalaria del registro español de implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) desde su inicio hasta el año 2018, y como objetivos secundarios otros eventos clínicos intrahospitalarios, la mortalidad total a los 30 días y la evaluación de cuál ha sido la evolución temporal de este registro.

Métodos: Fueron analizados todos los pacientes consecutivos incluidos en el registro español de TAVI. En este análisis temporal se dividió la población en pacientes tratados antes de 2014 (cohorte A: 2009-2013) y pacientes tratados entre los años 2014 y 2018 (cohorte B).

Resultados: Desde agosto de 2007 hasta junio de 2018 se incluyeron 7.180 pacientes. La edad media fue de 81,2 ± 6,5 años y el 53% eran mujeres. El EuroSCORE logístico fue del 12% (8-20). Se utilizó un acceso transfemoral en el 89%. La mortalidad total intrahospitalaria fue del 4,7% y a los 30 días fue del 5,7%. En el análisis temporal durante la fase hospitalaria, las tasas de infarto, accidente cerebrovascular, necesidad de marcapasos, taponamiento, obstrucción coronaria y complicaciones vasculares fueron similares en ambos grupos. Sin embargo, en la cohorte B se observó una reducción de la necesidad de conversión a cirugía y de malaposición de la válvula, y además la tasa de éxito del implante fue mayor (93 frente a 96%; p < 0,001). La mortalidad por cualquier causa ajustada tanto intrahospitalaria como a los 30 días, fue significativamente menor en la cohorte B (odds ratio [OR] = 0,65; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%], 0,48-0,86; p = 0,003; y OR = 0,71; IC95%, 0,54-0,92; p = 0,002, respectivamente).

Conclusiones: En el análisis temporal del registro español de TAVI se observan un cambio en el perfil clínico de los pacientes y una mejora en la evolución clínica tanto intrahospitalaria como a los 30 días en los pacientes tratados en los últimos años.

Palabras clave: Tratamiento transcatéter de la válvula aórtica. Registros. Estenosis aórtica grave.

Abbreviations: TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is the best therapeutic option today for most elderly patients with severe, degenerative aortic stenosis.1-4The evidence that supports this indication comes from rigorous randomized clinical trials conducted with balloon expandable valves5-7like self-expandable valves.8-10In this sense, this technique has recently consolidated after the publication of the initial results of new studies conducted in low-risk patients.11,12

Over the years, the implantation technique and the type of patients have changed.13,14These factors together with the new generations of valves including technical improvements have reduced the occurrence of major cardiovascular and cerebral events both in-hospital and in the long-term follow-up.15,16In the French TAVI registry (n = 16 969 patients) surgical risk was lower in the patients treated, a greater simplification of the technique via transfemoral access, and a lower short-term mortality rate over the last few years (2013-2015) compared to the first period studied (2010-2012). However, these differences were not found in the time trend analysis of the English registry (n = 3980).

The study primary endpoint was to present the in-hospital all-cause mortality rate of the Spanish TAVI registry from its inception until 2018. Secondary endpoints included other in-hospital clinical events, 30-day overall mortality, and a time trend analysis in 2 well-defined time periods: from August 2007 through December 2013 (cohort A), and from January 2014 through June 2018 (cohort B) by assessing the differences seen in the baseline clinical characteristics and the appearance of clinical events between both groups.

METHODS

The Spanish TAVI registry has been promoted by the board of directors of the Section of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Since 2010, all Spanish TAVI-capable centers are invited every year to participate in this registry and enter data from all the patients with severe, aortic stenosis treated with TAVI. These data come from the units of cardiology and cardiac surgery and are entered into a periodically reviewed online dedicated database. Although there is not such a thing as a formal audit, the data entered in the registry are systematically reviewed to look for inconsistencies or lack of data; the review is conducted by a database expert who contacts the centers to solve any incidents found. Over the years 46 Spanish centers have participated in the registry (annex 1 of the supplementary data) and although it started back in 2010, 232 patients treated between 2007 and 2009 have been entered retrospectively and included in the analysis.

In this study all consecutive patients included in the Spanish TAVI registry were analyzed. In the time trend analysis, the population was divided into patients treated before 2014 (cohort A: 2009-2013) and those treated between 2014 and 2018 (cohort B) since 2014 was the year when the new generation of the 2 most popular valves in our country were implanted for the first time: the Edwards and the CoreValve.

Study variables

Events were defined according to the recommendations established by the Valve Academic Research Consortium17in cohort A, and according to the recommendations designed by the Valve Academic Research Consortium II18in cohort B. High surgical risk was defined as a logistic EuroSCORE value > 20% and as a Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ risk model value > 8%.

Statistical analysis

After confirming the variables normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test), quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. Qualitative data were expressed as absolute value and percentage. To assess the predictors of in-hospital mortality, the multivariable logistics regression model was used. Variables with probability values < 0.1 in the univariable analysis or clinically relevant were included in the analyses. To assess the predictors of 30-day mortality the Cox backward stepwise regression model was used. Survival curve was obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method. Two-tailed P-values < .05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS.19

RESULTS

Total results

Baseline and procedural characteristics

From August 2007 through June 2018, 180 patients were included in the Spanish TAVI registry.7Mean age was 81.2 ± 6.5 years and 53% were women. Logistics EuroSCORE was 12% (8-20). Transfemoral access was used in 89% of the cases in 78% of which percutaneous puncture was used and surgical dissection in the remaining cases. The most commonly used valve was the CoreValve self-expandable system (49%) very closely followed by the balloon-expandable Edwards valve (46%). The most common valve size was number 26. The rate of successful device implantation was 94% (table 1and table 2).

Table 1. Baseline clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of the study patients

| Baseline characteristics | All patients (n = 7180) | Cohort A (years 2009-2013) (n = 3075) | Cohort B (years 2014-2018) (n = 4105) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age | 81.2 ± 6.5 7171 | 81.0 ± 6.4 3075 | 81.2 ± 6.7 4096 | .19 |

| Women | 3796 / 7166 (53.0) | 1636 / 3075 (53.2) | 2160 / 4091 (52.8) | .79 |

| Weight, kg | 72.6 ± 14 7087 | 70.9 ± 13 3069 | 72.1 ± 14 4018 | < .001 |

| Height, cm | 160 ± 9 6714 | 159 ± 9 2879 | 160 ± 9 3835 | < .001 |

| Body mass index | 28.01 ± 4.9 6838 | 27.99 ± 4.9 2879 | 28.16 ± 4.9 3959 | .143 |

| Hypertension | 5728 / 7081 (80.9) | 2437 / 3073 (79.3) | 3291 / 4008 (82.1) | .003 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3903 / 6698 (58.3) | 1586 / 2875 (55.1) | 2317 / 3823 (60.6) | < .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2447 / 6752 (36.2) | 998 / 2875 (34.7) | 1449 / 3877 (37.4) | .02 |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Previous stroke | 764 / 6797 (11.3) | 342 / 2879 (11.9) | 422 / 3918 (10.7) | .15 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1009 / 6903 (14.6) | 484 / 3071 (15.7) | 525 / 3832 (13.7) | .02 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2090 / 7105 (29.4) | 1231 / 3075 (40.0) | 1576 / 4030 (39.1) | .43 |

| Previous AMI | 919 / 6565 (13.9) | 396 / 2878 (13.7) | 523 / 3687 (14.2) | .62 |

| Previous PCI | 1476 / 6879 (21.4) | 651 / 3065 (21.2) | 825 / 3814 (21.6) | .70 |

| Previous revascularization surgery | 645 / 6689 (9.6) | 336 / 3059 (10.9) | 309 / 3630 (8.5) | .001 |

| Previous aortic valve replacement | 210 / 4245 (4.9) | 44 / 931 (4.7) | 166 / 3314 (5.0) | .73 |

| Previous mitral valve replacement | 81 / 4245 (1.1) | 6 / 931 (0.6) | 75 / 3314 (2.3) | .001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1905 / 7037 (27.1) | 855 / 3067 (27.9) | 1050 / 3970 (26.4) | .18 |

| Pacemaker | 520 / 7037 (7.3) | 216 / 3067 (7.0) | 304 / 3970 (7.6) | .33 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 55 ± 25 6638 | 50 ± 47 2874 | 58 ± 27 3764 | < .001 |

| Class III-IV dyspnea | 4726 / 6810 (69.4) | 2136 / 2877 (74.2) | 2590 / 3933 (66.8) | < .001 |

| Class III-IV angina | 567 / 7062 (8.0) | 303 / 3073 (9.8) | 264 / 3989 (7) | < .001 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 12 (8-20) 6738 | 14 (9-22) 3027 | 11 (7-18) 3711 | < .001 |

| STS score | 5 (3-9) 3190 | 7 (4-18) 1024 | 5 (3-7) 2166 | < .001 |

| High surgical risk | 2010 (28.0%) | 1139 (37%) | 871 (22%) | < .001 |

| Surgical contraindication | 1854 / 7180 (25.8) | 971 / 3075 (31.6) | 883 / 4105 (21.5) | < .001 |

| Preprocedural echocardiographic data | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 56.9 ± 13 6927 | 56.9 ± 14 3056 | 56.8 ± 13 3871 | .66 |

| Mean aortic transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 48 ± 15 6599 | 49 ± 15 3026 | 47 ± 15 3573 | < .001 |

| Peak aortic transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 79 ± 23 6606 | 81 ± 23 3033 | 77 ± 23 3573 | < .001 |

| Indexed valve area, cm2 | 0.65 ± 0.2 4267 | 0.62 ± 0.2 1679 | 0.68 ± 0.2 2588 | < .001 |

| Pulmonary artery pressure, mmHg | 47 ± 18 3046 | 48 ± 16 1188 | 47 ± 20 1858 | .17 |

| Diameter of aortic annulus, mm | 23.2 ± 3 3935 | 22.9 ± 2 1224 | 23.2 ± 3 2711 | .001 |

| Grade III-IV mitral regurgitation | 410 / 5857 (7.0) | 159 / 2368 (6.7) | 251 / 3489 (7.2) | .48 |

| Grade III-IV aortic regurgitation | 121 / 3172 (3.8) | 56 / 691 (8.1) | 65 / 2481 (2.6) | < .001 |

|

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ risk model. |

||||

Table 2. Procedural characteristics

| All patients (n = 7180) | Cohort A (years 2009-2013) (n = 3075) | Cohort B (years 2014-2018) (n = 4105) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | < .001 | |||

| Transaortic | 56 / 7180 (0.8) | 28 / 3075 (0.9) | 28 / 4105 (0.7) | |

| Subclavian axillary | 144 / 7180 (2.0) | 58 / 3075 (1.8) | 86 / 4105 (2.0) | |

| Transapical | 568 / 7180 (7.9) | 431 / 3075 (14.0) | 137 / 4105 (3.3) | |

| Transfemoral | 6412 / 7180 (89.3) | 2558 / 3075 (83.2) | 3804 / 4105 (92.6) | |

| Access route | .57 | |||

| Dissection | 1378 / 6225 (22.1) | 526 / 2417 (21.7) | 852 / 3808 (22.4) | |

| Puncture | 4847 / 6225 (77.8) | 1891 / 2417 (78.2) | 2956 / 3808 (77.6) | |

| Type of valve | < .0001 | |||

| Engager | 5 / 7180 (0.1) | 0 / 3075 (0) | 5 / 4105 (0.1) | |

| Direct Flow | 8 / 7180 (0.1) | 3 / 3075 (0.1) | 5 / 4105 (0.1) | |

| Allegra | 5 / 7180 (0.1) | 0 / 3075 (0.1) | 16 / 4105 (0.4) | |

| Lotus | 60 / 7180 (0.8) | 1 / 3075 (0.03) | 59 / 4105 (1.4) | |

| Symetis | 105 / 7180 (1.5) | 0 / 3075 (0) | 105 / 4105 (2.6) | |

| Portico | 172 / 7180 (2.4) | 0 / 3075 (0) | 172 / 4105 (4.1) | |

| Edwards | 3309 / 7180 (46.1) | 1468 / 3075 (47.7) | 1841 / 4105 (44.8) | |

| CoreValve | 3516 / 7180 (48.9) | 1603 / 3075 (52.1) | 1913 / 4105 (46.6) | |

| Valve size | < .001 | |||

| 23 | 1746 / 6712 (26.0) | 742 / 2865 (25.9) | 1004 / 3847 (26.1) | |

| 26 | 2742 / 6712 (40.9) | 1402 / 2865 (48.9) | 1340 / 3847 (34.8) | |

| 29 | 1791 / 6712 (26.7) | 681 / 2865 (23.8) | 1110 / 3847 (28.8) | |

| > 29 | 247 / 6712 (3.6) | 37 / 2865 (1.2) | 210 / 3847 (5.4) | |

| Other sizes | 186 / 6712 (2.7) | 3 / 865 (0.04) | 183 / 3847 (4.7) | |

| Predilatation | 2072 / 3748 (55.3) | 707 / 809 (87.4) | 1365 / 2939 (46.4) | < .0001 |

| Posdilatation | 1457 / 6767 (21.5) | 561 / 3071 (18.3) | 897 / 3696 (24.3) | < .0001 |

| Room | < .0001 | |||

| Operating room | 288 / 7180 (4.0) | 223 / 3075 (7.2) | 65 / 4105 (1.5) | |

| Catheterization laboratory | 6575 / 7180 (91.6) | 2759 / 3075 (89.7) | 3816 / 4105 (92.5) | |

| Hybrid room | 317 / 7180 (4.4) | 93 / 3075 (3.0) | 224 / 4105 (5.4) | |

| Duration, minutes (mean ± standard deviation) | 105 ± 45 | 106 ± 47 | 105 ± 43 | .48 |

| Median | 95 (72-121) 5514 | 95 (72-122) 2834 | 95 (72-120) 2680 | .94 |

| Length of hospital admission, days (mean ± standard deviation) | 8.3 ± 8 | 8.6 ± 8 | 8.0 ± 7 | .002 |

| Median | 6 (5-9) 6459 | 6 (5-9) 2751 | 6 (4-8) 3708 | .15 |

| Successful implantation | 6778 / 7153 (94.8) | 2848 / 3062 (93.0) | 3930 / 4091 (96.1) | < .001 |

In-hospital and follow-up complications

The rates of in-hospital acute myocardial infarction, stroke, vascular complications, and hemorrhages were 0.9%, 1.9%, 10.7%, and 7.6%, respectively. Pacemaker implantation was required in 14% of the cases. The rates of overall in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality were 4.7% and 5.7%, respectively (table 3).

| All | Cohort A (years 2009-2013) (n = 3075) | Cohort B (years 2014-2018) (n = 4105) | P | Non-adjusted OR | Adjusted OR | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion to surgery | 58 / 7076 (0.8) | 34 / 3005 (1.1) | 24 / 4062 (0.6) | .013 | 0.52 (0.31-0.88) | 0.49 (0.24-0.98) | .04 |

| Tamponade | 57 / 6899 (0.8) | 19 / 2900 (0.7) | 38 / 3999 (1.0) | .18 | 1.45 (0.83-2.56) | 2.17 (1.08-3.85) | .03 |

| Coronary obstruction | 23 / 6889 (0.3) | 12 / 2897 (0.4) | 11 / 3992 (0.3) | .33 | 0.66 (0.29-1.52) | 0.69 (0.28-1.69) | .42 |

| Malapposition | 153 / 6884 (2.2) | 92 / 2897 (3.2) | 61 / 3987 (1.5) | < .001 | 0.47 (0.34-0.66) | 0.46 (0.32-0.66) | .001 |

| Migration | 119 / 6884 (1.7) | 76 / 2897 (2.5) | 43 / 3987 (1) | ||||

| Embolization | 12 / 6884 (0.2) | 2 / 2897 (0.1) | 10 / 3987 (0.2) | ||||

| Unknown | 22 / 6884 (0.3) | 14 / 2897 (0.2) | 8 / 3987 (0.1) | ||||

| AMI | 64 / 7055 (0.9) | 28 / 3053 (0.9) | 36 / 4001 (0.9) | .94 | 0.98 (0.60-1.61) | 0.97 (0.53-1.79) | .93 |

| Vascular complications | 769 / 7055 (10.7) | 268 / 3053 (8.8) | 501 / 4001 (12.5) | < .001 | 1.49 (1.27-1.72) | 1.18 (0.98-1.41) | .09 |

| Hemorrhages | 544 / 7054 (7.6) | 169 / 3053 (5.5) | 375 / 4001 (9.4) | < .001 | 1.75 (1.47-2.13) | 1.79 (1.43-2.22) | < .001 |

| Renal complications | 377 / 7054 (5.3) | 140 / 3053 (4.6) | 237 / 4001 (5.9) | .01 | 1.32 (1.05-1.61) | 1.32 (1.03-1.69) | .028 |

| Stroke | 133 / 7055 (1.9) | 55 / 3053 (1.8) | 78 / 4001 (1.9) | .65 | 1.09 (0.76-1.54) | 0.84 (0.55-1.28) | .43 |

| Pacemaker | 1016 / 7092 (14.3) | 416 / 3053 (13.6) | 600 / 4001 (15.0) | .14 | 1.11 (0.96-1.27) | 0.99 (0.84-1.16) | .91 |

| In-hospital mortality | 340 / 7054 (4.7) | 200 / 3053 (6.6) | 140 / 4001 (3.5) | < .001 | 0.52 (0.41-0.65) | 0.65 (0.48-0.86) | .003 |

|

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio. |

|||||||

Results of the time trend analysis

Baseline and procedural characteristics

No differences were found between the groups regarding the patients’ mean age and sex. However, cohort B had more cardiovascular risk factors and surgeries performed prior to mitral valve implantation, but less peripheral vascular disease. Although the rate of coronary artery disease was similar in both groups, previous surgical coronary revascularizations were less common in cohort B. Creatinine clearance values were higher in cohort B. Regarding the clinical situation, the presence of severe symptoms (functional class III-IV) both for dyspnea (New York Heart Association) and angina (Canadian classification) was significantly lower in cohort B. Surgical risk was significantly lower in cohort B according to the logistics EuroSCORE and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ risk model. There were fewer inoperable patients or high surgical risk patients in cohort B as well. In this group, the severity of stenosis was lower (larger indexed valve area, lower transvalvular mean gradient) and annular diameter was larger. Regarding the route of access, the use of transfemoral approach started to grow back in 2014 (from 83% to 94%) mainly because the use of transapical access dropped from 14% to 3%. The type of valve used was almost exclusively the Edwards SAPIEN XT while the CoreValve was used in cohort A. In cohort B the new generations of these valves were used (Edwards SAPIEN 3 and Evolut R) as well as other types of self-expandable valves like the Portico (4.1%), the ACURATE neo (2.6%). and the Lotus valve (1.4%). The most common size of the valves was 26 mm in both groups. The rate of predilatation decreased in cohort B, but the rate of postdilatation grew. The rate of successful implantation increased significantly over the last period from 93% (cohort A) to 96% (cohort B). The working space where the TAVI was performed changed as well; although the cardiac catheterization laboratory was the most common working space in both cohorts fewer valves were implanted in the operating room and more valve were implanted in hybrid operating rooms in cohort B.

In-hospital and 30-day follow-up events

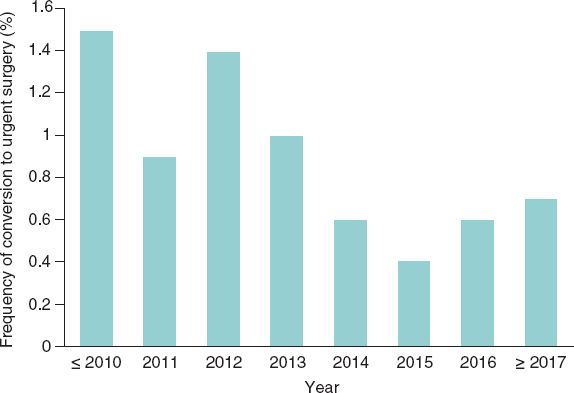

The length of hospital admission was reduced significantly in cohort B. In the hospital stage, the rates of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, need for pacemaker, and coronary obstruction were similar in both groups. However, the conversion rate to surgery (figure 1) and valve malapposition dropped significantly in patients treated from 2014. No inter-group differences were found regarding vascular complications. However, the overall rate of hemorrhages and renal complications were higher in cohort B. In-hospital all-cause mortality was significantly lower in cohort B with a 47% reduction (odds ratio [OR], 0.65; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.48-0.86; P= .003).

Figure 1. Conversion rate to urgent surgery through the years.

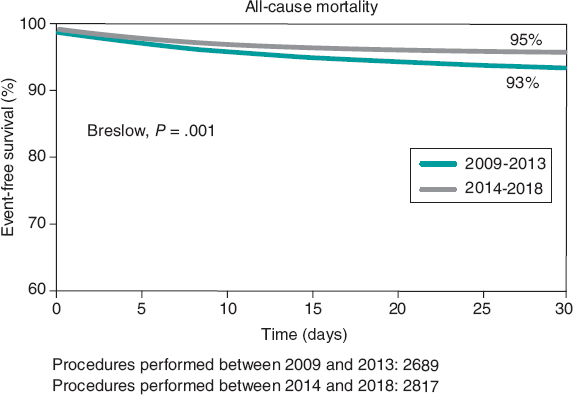

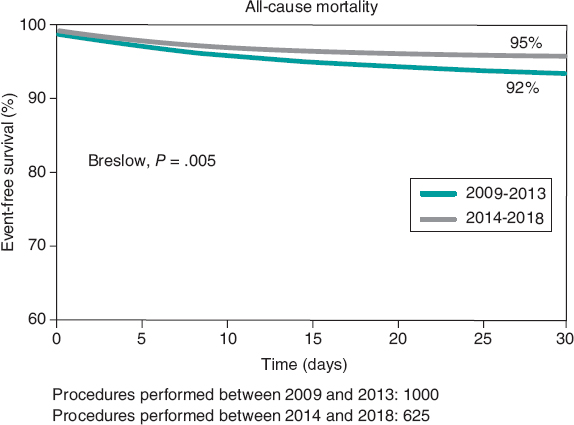

Mortality rate dropped 32% at the 30-day clinical follow-up in cohort B (6.9 vs 4.7%) (OR, 0,71; 95%CI, 0.54-0.92; P= .002) (figure 2and figure 3). The 30-day mortality predictors are shown on table 4.

Figure 2. Survival rate at the 1-year follow-up of patients included in the Spanish TAVI registry treated in 2009-2013 and 2014-2018.

Figure 3. Survival rate at the 1-year follow-up of high surgical risk patients only treated in 2009-2013 and 2014-2018.

Table 4. Independent predictors of mortality at the 30-day follow-up

| Variables predictors of death at the 30-day follow-up | Univariate OR (95%CI) | P | Adjusted multivariate OR (95%CI) before the procedure | P | Adjusted multivariate OR (95%CI) before and after the procedure | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | ||||||

| Years 2014-2018 | 0.52 (0.41-0.65) | < .001 | 0.59 (0.46-0.76) | < .001 | 0.71 (0.54-0.92) | .01 |

| Body mass index | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | .007 | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.93 (0.74-0.93) | .54 | 0.94 (0.74-1.21) | .64 | 0.89 (0.69-1.14) | .35 |

| Creatinine clearance | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | < .001 | * | * | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.49 (1.13-1.97) | .005 | * | * | ||

| Mean aortic gradient, mmHg | 1.003 (0.99-1.01) | .47 | 1.002 (0.99-1.01) | .57 | 1.003 (0.99-1.01) | .54 |

| Grade III-IV mitral regurgitation | 1.98 (1.34-2.92) | .001 | * | * | ||

| Grade III-IV aortic regurgitation | 2.06 (1.01-4.19) | .05 | * | * | ||

| Grade III-IV angina | 1.08 (0.73-1.61) | .69 | 1.16 (0.76-1.78) | .50 | 1.16 (0.74-1.81) | .52 |

| Grade III-IV dyspnea | 1.48 (1.13-1.96) | .005 | * | * | ||

| Surgical risk | 1.38 (1.09-1.74) | .007 | 1.33 (1.03-1.71) | .029 | 1.26 (0.96-1.64) | .09 |

| Postoperative | ||||||

| Transfemoral access | 0.50 (0.38-0.66) | < .001 | 0.49 (0.36-0.67) | < .001 | ||

| Successful implantation | 0.10 (0.08-0.13) | < .001 | 0.11 (0.09-0.15) | < .001 | ||

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. *These variables were not part the model because they are used to estimate surgical risk. |

||||||

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were: a)in Spain there is a time trend in the type of patients treated with TAVI through the years; b)there have been changes, transfemoral access has become widely used, postdilatation has increased, and the rates of valve malapposition and conversion to surgery have dropped. And the most important thing of all, there has been a significant increase in the rate of successful implantation since 2014; and c)there is a significant reduction of in-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality in patients treated from 2014.

Differences in baseline characteristics

This study saw a time change in the risk profile of patients treated with TAVI in Spain. The percentage of high-risk patients over the first period was 37% vs 22% from 2014 onwards. These findings are consistent with those reported in the time analysis of the French registry15where the logistics EuroSCORE dropped from 21.7 ± 14.2% to 17.9 ± 12.3%. In this sense, the facts that may explain these findings are the appearance of randomized clinical trials that use TAVI in lower-risk patients.2,7From 2015 to 2016 the results from the NOTION (The Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention) and PARTNER II (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) clinical trials—on low-and-intermediate risk patients—were published. The NOTION trial did not find any significant differences between patients treated with TAVI or surgical aortic valve replacement regarding the composite endpoint of death, stroke or acute myocardial infarction at the 1 and 5-year follow-up. The PARTNER II clinical trial7randomized 2032 intermediate risk patients to be treated with TAVI or surgery. No significant differences were found in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke at the 2-year follow-up. However, when only the cohort treated with transfemoral access was studied, TAVI showed significantly lower rates of death and disabling stroke.

Procedural differences

This study describes the time changes that seem to impact the higher rate of successful implantation, a factor closely related to mortality. The difference found would be fewere cases of malapposition. Also, an increase of transfemoral access has been reported. All these changes are explained by the greater experience gained with the implantation technique that is focused on simplification and the improvements made in valve design. All through 2014, a new generation of valves (Edwards SAPIEN 3 and Evolut R) were implanted for the first time with technical breakthroughs like the smaller release system and greater use of transfemoral access seen in cohort B. The introduction of the outer skirt was associated with a lower rate of perivalvular leak, higher procedural success, and less need for valve overexpansion. This reduces potentially the rate of annular tear and need for conversion to surgery (a high mortality procedure). Also, in the case of the Evolut R valve the introduction of a fully retrievable platform may have lowered the rate of valve malapposition and increased the rate of successful implantation seen from 2014.

Reduced mortality

Back in 2013 the data of 1416 patients included in the years 2010 and 2011 in the Spanish TAVI registry were published.19In this analysis the rate of successful implantation was 94% and the in-hospital mortality rate 8%. In this study the overall mortality rate was 4.7%. A remarkable aspect of the Spanish registry time analysis is that it shows a clear mortality reduction over the second period studied (cohort B) regardless of the patients’ baseline characteristics. These results are consistent with the French registry time analysis that showed reduced in-hospital and 30-day mortality in the patients included in the 2013-2015 period.15On the contrary, in the English registry time analysis16from 2007 through 2012, no differences were found in the patients’ baseline characteristics or surgical risk studied through those years. However, there was a higher percentage of patients with ventricular dysfunction. In this registry, mortality reduction and shorter hospital stays were only seen over the first 2 years of follow-up in the patients treated back in 2012. The authors explain these results by the greater experience gained in the better selection of patients who may benefit the most from TAVI, something that may have also affected the results of this study.

In this registry, as it occurred in the French one, there was a higher rate of tamponade over the last period studied. However, the conversion rate to surgery was lower, suggestive that the consolidation of the procedure and the early diagnosis of complications may have influenced the results.

A remarkable aspect is the higher overall rate of hemorrhages and renal dysfunction seen in cohort B. These results should be interpreted with caution because there are no data on the severity and cause for these events. However, given the reduced mortality seen in this period, it can be concluded that there is no significant increase of major hemorrhages, although this is just speculation due to the lack of data on this regard.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that it is a registry whose data have not been audited externally. Also, it is a voluntary registry that does not include all Spanish centers with TAVI-capabilities. Certain variables appear in 50% of the patients, which is something exceptional if we consider that most variables are present in 90% of the cases. The degree and causes for vascular complications (hemorrhage and renal failure) are not available and data should be interpreted with caution. On the other hand, the change in the adjudication of events derived from the different definition used over the first and second periods (Valve Academic Research Consortium and Valve Academic Research Consortium II, respectively) may vary in some patients although this would be an exception.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows the better risk profile and more successful implantation rate of patients treated over the last few years. This has reduced in-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. María José Pérez-Vizcayno for her contribution during the entire process of database review and statistical analysis. The authors also wish to thank all the people and participant centers involved in the national Spanish TAVI registry.

FUNDING

The Section of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology sponsors the maintenance and exploitation of the database.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R. Trillo-Nouche is a proctor of TAVI valves for Medtronic and Boston Scientific. M. Pan has participated and received funds for the lectures given on behalf of Abbott, Terumo Medical Corporation, and Philips Volcano. R. Moreno is an associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the editorial protocol of the journal was observed to guarantee an impartial manuscript handling. R. Moreno has participated and received funds for lectures, counsel, and congress attendance on behalf of Edwards Lifesciences, and is a proctor of the Lotus and ACURATE neo valves (both from Boston Scientific). Also, R. Moreno has participated and received funds for the lectures, counsel, and congress attendance on behalf of Boston Scientific, and is a proctor of the Allegra valve from New Vascular Therapy. I. Amat-Santos is a proctor of Boston Scientific. R. Romaguera has participated and received funds from Medtronic and Palex Medical. A. Pérez de Prado has participated and received funds for counseling provided to Boston Scientifice iVascular, and for the lectures given on behalf of Abbott, B Braun Surgical, Terumo Medical Corporation, and Philips Volcano. L. Nombela-Franco is a proctor for Abbott and has participated and received funds for lectures given on behalf of Edwards Lifesciences. F. Alfonso is an associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology. The journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. J.M. de la Torre Hernández is the editor-in-chief of REC: Interventional Cardiology. The journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- In national registries like the French one, a time change in the clinical profile and progression of patients treated with TAVI has been confirmed. However, these findings have not been made in the time analysis of the English registry.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The main contribution of this study is the publication of all data from our national database. Also, that results will be included in the medical literature and that the time change seen in the profile of patients and clinical results is indicative of a growing experience with the implantation technique and improvements in valve design

REFERENCES

1. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187-2198.

2. Thyregod HG, Steinbrüchel DA, I hlemann N, et al. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis:1-Year Results From the All-Comers NOTION Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2184-2194.

3. Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366: 1696-1704.

4. Thourani VH, Kodali S, Makkar RR, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients:a propensity score analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:2218-2225.

5. Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1686-1695.

6. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597-1607.

7. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609-1620.

8. Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1790-1798.

9. Popma JJ, Adams DH, Reardon MJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement using a self-expanding bioprosthesis in patients with severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1972-1981.

10. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic- Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321-1331.

11. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

12. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1706-1715.

13. Islas F, Almería C, García-Fernández E, et al. Usefulness of echocardiographic criteria for transcatheter aortic valve implantation without balloon predilation:a single-center experience. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:423-429.

14. García E, Almería C, UnzuéL, Jiménez-Quevedo P, Cuadrado A, Macaya C. Transfemoral implantation of Edwards Sapien XT aortic valve without previous valvuloplasty:role of 2D/3D transesophageal echocardiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84:868-876.

15. Auffret V, Lefevre T, Van Belle E, et al. Temporal Trends in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in France:FRANCE 2 to FRANCE TAVI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:42-55.

16. Ludman PF, Moat N, de Belder MA, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the United Kingdom:temporal trends, predictors of outcome, and 6-year follow-up:a report from the UK Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) Registry, 2007 to 2012. Circulation. 2015;131:1181-1190.

17. Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation clinical trials:a consensus report from the Valve Academic Research Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:205-217.

18. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation:the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2403-2418.

19. SabatéM, Cánovas S, García E, et al. In-hospital and mid-term predictors of mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation:data from the TAVI National Registry 2010-2011. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:949-958.