Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Spain was inducted in the European initiative Stent for Life in a ceremony hosted by the General Assembly of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) back in 2009. As president of the Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC), Dr. Fina Mauri signed the declaration of commitment with this initiative aimed to improve the access of patients to reperfusion by the increasing use of primary percutaneous coronary interventions (pPCI) as the optimal treatment in the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

The Stent for Life initiative was born the previous year (September 2008) as an alliance among the Spanish Society of Cardiology, EAPCI, and Eucomed.1 In Europe the situation of reperfusion in the management of infarction was under discussion. They came to the conclusion that there was a great heterogeneity among the different countries with an overall scarce penetration of pPCI as the treatment of choice.2 These differences were not related to gross domestic product (GDP): countries with relative low GDPs (Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Poland, Lithuania) performed many more pPCIs per million inhabitants compared to other countries with higher GDPs like Spain.2 For this reason, Spain was among the 6 countries asked to participate in this initiative together with Turkey, France, Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia. All performed less than 200 pPCIs per million inhabitants (in 2008 only 165 PCIs per million inhabitants were performed in Spain). The objectives established at that time are shown on table 1; they were numerical objectives of implementation and penetration of this technique in the management of STEMI with the implicit creation of acute myocardial infarction networks.

Table 1. Objectives of the Stent for Life initiative from 2008

| Define regions/countries with unmet medical needs for the implementation of the optimal management of acute coronary syndrome |

|---|

| Implement an action program to increase the access of patients to pPCIs: a) Increase the percentage of pPCIs performed in > 70% of STEMI patients b) Achieve pPCI rates > 600 per million inhabitants/year c) Offer a 24/7 service in all necessary angioplasty centers for the full coverage of the region/country |

|

pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

Back in 2008, there were only 4 well-structured infarction networks across in Spain: Murcia, Galicia, Balearic Islands, and the Chartered Community of Navarre performed between 200 and almost 400 pPCIs per million inhabitants. However, eventually only 12.8% of the entire Spanish population benefited from these 4 networks. In the remaining autonomous communities, the pPCIs were performed erratically with numbers lower or closer to 100 pPCIs per million inhabitants. Regions like the Community of Valencia, the Principality of Asturias, and Andalusia performed 61, 78, and 106 pPCIs per million inhabitants).3 Like Europe, these regional differences were not related to the GDP of the different Spanish autonomous communities. Therefore, the creation of a myocardial infarction network with full hospital infrastructure, trained professionals, and a system of medical emergencies in a developed country like ours became a purely organizational matter. In October 2010 and with the explicit support from the SEC and its affiliate sections Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology, Ischemic Heart Disease, and Coronary Units the different scientific societies of the autonomous communities signed the declaration of membership to the Stent for Life initiative (figure 1). From that moment on, the focus was on 3 different levels for the progressive and gradual implementation of infarction networks. In the first place, there was a political and media approach to the different health administrations involved. The publication of the comparative results from the different autonomous communities in the media (figure 2) contributed effectively to their involvement in this issue. Parallel to this and thanks to scientific publications and cardiology meetings, professionals became aware on the clinical need to implement these infarction networks.4-7 Finally, patients were approached through commercial campaigns and media announcements with positive short-term results.8 Everything was mostly funded with the unconditional support from the industry. After 10 years of many people working for the Stent for Life initiative it can be said that it has contributed to the implementation of infarction networks nationwide. In 2018, 21 261 pPCIs were performed (13 395 back in 2008) with an average rate of 416 pPCIs per million inhabitants. This rate is considered adequate given the prevalence of ischemic heart disease in our country without great differences among the different autonomous communities.9 At this point, what challenges will the next decade bring? The survey of a paper recently published by Rodriguez-Leor et al.10 in REC: Interventional Cardiology may have some of the answer to this question. The current objectives should focus on both the patient and the healthcare provider. At this point it is not about opening new centers or programs anymore, but about designing the procedures required for each center to keep quality outcomes. The satisfaction of well-trained professionals built on adequate retributions, regulating the rest periods, and the correct sizing of staff based on the healthcare needs are all key issues to take into consideration at the infarction centers. Similarly, generational replacement should occur while keeping the quality of the entire process. The Administration should consider payment to centers based on results and make sure that these payments reach the treating physician. On the other hand, very complex cases like STEMI patients complicated with cardiogenic shock should be referred to specialized centers capable of performing advanced ventricular assist techniques, heart surgery, and transplants. In this type of patients, mortality rate is still very high (around 50%). Therefore, each infarction network should be able to identify its shock centers for the adequate management of these patients.

Figure 1. A: induction ceremony of the scientific societies of the different autonomous communities into the Stent for Life initiative (Madrid, October 4, 2010); B: certificate of membership to the Stent for Life initiative of an affiliate society (Society of Cardiology of Castile and León).

Figure 2. Examples of news published by the media on comparative results among different autonomous communities on the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

In conclusion, the objectives of the Stent for Life initiative in our country should look at the new clinical and professional challenges ahead with the patient as the protagonist of all clinical actions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Matías Feldman, Dr. Ander Regueiro, Dr. José Ramón Rumoroso, and Dr. Miren Tellería for their dedication to the Stent for Life initiative in Spain over the last 10 years. We also wish to thank the members of the different boards of directors of the Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology Section of the SEC for their contribution to this paper.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M. Sabaté was the national coordinator of the Stent for Life initiative in Spain between 2009 and 2013. No other conflicts of interest have been reported.

REFERENCES

1. Widimsky P, Wijns W, Kaifoszova Z. Stent for Life:how this initiative began? EuroIntervention. 2012;8 Suppl P:P8-10.

2. Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe:description of the current situation in 30 acountries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943-957.

3. Baz JA, Pinar E, Albarrán A, Mauri J;Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. 17th official report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology (1990-2007). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:1298-1314.

4. Kristensen SD, Fajadet J, Di Mario C, et al. Implementation of primary angioplasty in Europe:Stent for Life initiative progress report. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:35-42.

5. Kristensen SD, Laut KG, Fajadet J, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction 2010/2011:current status in 37 ESC countries. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1957-1970.

6. Regueiro A, Bosch J, Martín-Yuste V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a European ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction network:results from the Catalan Codi Infart network. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009148.

7. Gómez-Hospital JA, Dallaglio PD, Sánchez-Salado JC, et al. Impact on delay times and characteristics of patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the southern metropolitan area of Barcelona after implementation of the infarction code program. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65:911-918.

8. Regueiro A, Rosas A, Kaifoszova Z, et al. Impact of the “ACT NOW. SAVE A LIFE“public awareness campaign on the performance of a European STEMI network. Int J Cardiol. 2015;197:110-112.

9. Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. Available online: https://www.hemodinamica.com/cientifico/registro-de-actividad/. Accessed 3 Jul 2019.

10. Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid-Alvarez A, Moreno R, et al. Survey on the needs of primary angioplasty programs in Spain. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:8-14.

Corresponding author: Sección de Cardiología Intervencionista, Instituto Cardiovascular, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain.

E-mail address: masabate@clinic.cat (M. Sabaté).

Undertaking the project REC: Interventional Cardiology, a bilingual journal published in English and Spanish and devoted to interventional cardiology seems a gigantic task to implement, which is why we wish to thank the editors for their entrepreneurial spirit and also Revista Española de Cardiología for making space for this new project. A unique opportunity for developing agreements and team work for the entire Spanish-speaking cardiological community that often feels the imposing presence of English-speaking scientific journals.

Combining the organizational and academic trajectory and leadership of the Spanish Society of Cardiology and the vitality, thrust, and enthusiasm of the Latin American interventional cardiology community may be the beginning of a huge agreement of productivity and novelty. This may, in turn, help the communication network between the Spanish vision planted at the very heart of Europe and the Latin American one that influences over 600 million people, thereby exponentially increasing the opportunities of communication for members of scientific societies and the possibilities of providing relevant scientific information. Talent is universal, opportunities are not.

Although European and American clinical practice guidelines on evidence-based medicine have tremendous exposure and each country publishes its own guidelines, we have been unable to integrate these concepts in regional or intersociety guidelines or approved documents. Yet at the Latin American Society of Interventional Cardiology (Sociedad Latinoamericana de Cardiología Intervencionista, SOLACI) we have tried to integrate the interventional guidelines established by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the American College of Cardiology. REC: Interventional Cardiology could well serve as a forum for all interventional cardiology guidelines and consensus documents of our region.

We should also mention that several clinical trials, series, and clinical cases studied in Latin America, especially those including international collaborations or inter-society agreements, should be published in this journal.

Although most multicentric randomized evidence-based clinical trials that are conducted in the United States and Europe are published in English, many significant advances made in cardiovascular medicine such as saphenous vein grafts used in coronary artery bypass graft surgery, stents, and stent-grafts have come from doctors within our region, such as R.G. Favaloro, J. Palmaz, and J.C. Parodi. However, even though these advances may speak Spanish, they have been implemented by English-speaking countries, which is the main reason why cooperation and integration should be our guiding spirit. The goal of this journal is to contribute, not to compete.

Needless to say that the success of this project depends entirely on us; all interventional cardiologists in Ibero-America should convince ourselves that we are capable of producing quality educational material that is attractive, not only to us, but also to our colleagues in other specialties, both in Latin America and the rest of the world. We are convinced that this will be so.

80% of the teachers predict that by 2026 digital content will replace print. In this sense, the educational resources that turn learning into a videogame, such as virtual reality or gaming, and that are patrimony of the digital world1, will make learning a more interactive experience. The digital format of REC: Interventional Cardiology, with its tremendously dynamic character and adaptability to the user, will help amplify its educational purpose, making it an addictive yet healthy experience.

In the battle to conquer everyone’s attention, sensationalist tabloid-style material seems to have replaced academic writing. The focus should be on getting the attention of the specialists through an updated informative model that never loses its primary educational purpose.

Sitting talent and different visions at the same table multiplies the options of creativity. REC: Interventional Cardiology is a golden opportunity for generating knowledge, healthy controversy, and pushing the Latin American interventional medical practice to the limit, under the mentoring of Revista Española de Cardiología in an effort to make a useful and enriching difference in the final result published.

This will be a privileged stage for exchange and academic contribution for the Ibero-American interventional cardiology communities. Congratulations and best wishes!

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever regarding this manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Kali B. The Future of Education and Technology. Available at: https://elearningindustry.com/future-of-education-and-technology. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Corresponding author: Fundación Favaloro, Avda. Belgrano 1746, C1093 Buenos Aires, Argentina.

E-mail addresses: omendiz@ffavaloro.org (O.A. Mendiz).

To this day, heart transplant is the treatment of choice in patients with heart disease and functional repercussions that is refractory to treatment (both drugs and electrical or mechanical devices) and has no contraindications. The milestone that made heart transplant take the spotlight in the management of these patients was the introduction of calcineurin inhibitors as basic immunosuppressants, which allowed the effective control of acute graft rejection. Immunosuppression patterns based on cyclosporine at the beginning and then on tacrolimus have led to really long survivals with means of up to 12 years.1 After acute rejection was no longer the main cause of graft failure and occasionally the patient, the long-term survival of the graft is basically limited by the development of coronary vascular disease.

Graft vascular disease represents an accelerated phase of the underlying fibroproliferative process that affects the entire coronary vascular bed diffusely. On the pathological analysis, its appearance is different from classic atherosclerosis of complex and multifactor etiology in that it includes non-immunity factors and, in particular, immunity factors.2 As a matter of fact, it is the most conspicuous manifestation of antibody-mediated late rejection, which is why it has sometimes been referred to as “chronic graft rejection”. Its incidence based on the angiographic data we have is over 30%-50% from the third to the fifth year after the transplant which has a significant impact on prognosis: it is the leading cause of graft failure and one of the leading causes of death in recipients with long survival rates.3 Also, the management of this process is relatively limited because of its diffuse nature that makes coronary revascularization procedures more difficult.

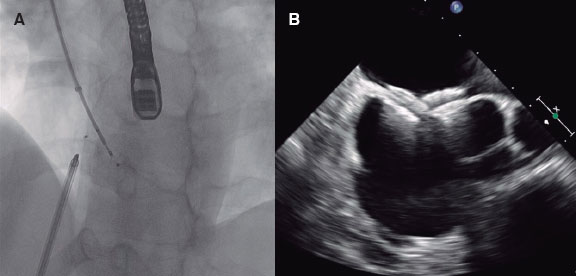

In the study conducted by Solano-López Morel et al.4 and recently published on REC: Interventional Cardiology, authors from 2 experienced groups revealed their results with percutaneous revascularization with drug-eluting stents in one of the most severe forms of graft vascular disease: chronic total coronary occlusion. The authors confirmed that the technique was feasible since it used state-of-the-art diagnostic and therapeutic technological means, although they restricted it to highly selected patients. The findings show that chronic total coronary occlusion has a low but still significant prevalence (12.2% of the patients), late onset (mean, 10 years after the transplant), and even in experienced hands it is barely eligible for percutaneous revascularization (13.5% of the patients with chronic total coronary occlusions). Although the angiographic results are promising (93% of initial success and 2% restenosis only), the prognosis of these patients is still poor (a 21.4% cardiovascular mortality rate with a mean at follow-up of 2.8 years) even compared to graft vascular disease without complete occlusion treated percutaneously (21.4% vs 8.3%). Although the study sample is limited, it would have been interesting to draw a comparison between patients with chronic total coronary occlusions treated percutaneous or medically.

The most important thing of the study conducted by Solano-López Morel et al.4 is that it is the first time that the feasibility of the recanalization of chronic total coronary occlusions in graft vascular disease is ever reported. The results are indicative that in these patients, percutaneous procedures are nothing more than palliative care sensu stricto whose effectiveness in clinical terms has not been confirmed yet (and probably never will). This comes as no surprise since graft vascular disease is a diffuse and progressive disease that affects both the epicardial coronary arteries and the intramyocardial trajectories and especially the capillary bed. Therefore, same as it happens with other conditions, the most effective management is preventive treatment targeted at well-known etiopathogenic factors including taking good care of the donor, preventing graft primary failure, preventing and treating cytomegalovirus-related infections, the universal use of statins (such as hypolipemiant and immunomodulating statins), and preventing antibody-mediated acute and chronic cell rejection through the use of individual immunosuppression therapies for each patient.5

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. González-Vílchez F, Almenar-Bonet L, Crespo-Leiro MG, et al. Spanish Heart Transplant Teams;collaborators in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry, 1984-2017. Spanish Heart Transplant Registry. 29th Official Report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Heart Failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:952-960.

2. Hernandez JM, de Prada JA, Burgos V, et al. Virtual histology intravascular ultrasound assessment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy from 1 to 20 years after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:156-162.

3. Chih S, Chong AY, Mielniczuk LM, Bhatt DL, Beanlands RS. Allograft Vasculopathy:The Achilles'Heel of Heart Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:80-91.

4. Solano-López Morel J, Fernández-Díaz JA, Martín Yuste V, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions of chronic total occlusions in heart transplant recipients. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:152-160.

5. Tremblay-Gravel M, Racine N, de Denus S, et al. Changes in Outcomes of Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy Over 30 Years Following Heart Transplantation. JACC Heart Fail.2017;5:891-901.

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Valdecilla Sur 1ª planta - pasillo 2, Avda. Valdecilla s/n, 39008 Santander, Cantabria, Spain.

E-mail address: cargvf@gmail.com (F. González Vílchez).

When Prometheus’ liver was daily devoured by the eagle that Zeus would send each day to the Caucasus mountains where the titan was kept in chains, pain was the price to pay for disobedience and immortality. Prometheus’ insurrection was sealed after he stole the fire from the gods and gave it to men so they could heat themselves, cook food, make utensils, and have a divine spark inside of them to become spiritual and intelligent beings, thus bringing them a little closer to the gods and away from the animal kingdom. The immortal nature of Prometheus would regenerate the liver only to see it devoured again the next day. Only Hercules put an end to Prometheus’ torment when he broke the chains of his sentence.

This Greek myth of the demi-god is a good analogy of the evolution of medicine from ancient to modern times. Suffering; disease; wisdom; hope; cure, and eventually immortality. It has been the greed shown by Homo sapiens that has tried to conquer the fire stolen by the Greek hero.

It is precisely this human exchange that has allowed us to evolve as a species. We have been able to conquer our planet, cure diseases, control epidemics, and fight our kind to the benefit but also to the detriment of our own world and at the expense of the extinction of millions of species, the very subjugation of death, and the suffering of millions of our own people.

Throughout history, doctors have been perceived by others has holders of some sort of a special talent. The first physicians were healers, shamans who understood the laws of the ancient universe and had a special connection with the divine. In addition to having a secret knowledge of plants, herbs, and minerals with healing potential, their wisdom had been transmitted through oral tradition from one family to the other or through genetic inheritance as some sort of natural selection of only those individuals with the necessary conditions to become healers. These were exceptional individuals among the ancient human groups who were measured by the highest standards and revered by the different societies. They were possibly Prometheus’ chosen ones as holders of that “extra fire”.

Medical science evolved with extraordinary advances for all mankind by drastically reducing child mortality at the end of the 20th century, improving life expectancy in most countries up to 75 years of age (by 2050 the estimates are that human beings will live up to 100 years old), and ultimately by managing successfully most of the diseases that plague the Homo sapiens.1

After the Second World War, medicine was revolutionized, a sort of golden age if you will, with the appearance of antibiotics, vaccines, new anesthetic agents, breaking surgical procedures, and new drugs. Doctors were respected and admired; the doctor-patient interchange was based on conversations and deep scrutiny of the intimate life of individuals and rigorous physical examinations following all rules of semiology.

These advances were followed by universal medical plans and health reforms, making medicine lose its human dimension of that doctor-patient relationship. Thus, the infamous “cost-benefit” ratio became a priority and technology was incentivized creating a gap between humanity and science and, on many occasions, verbal communication, so essential to understand each other, was simply gone and doctors became technicians or service providers overnight whose effectiveness was put under the microscope.

This was the birth of the so-called “junk consultation” that leads to countless complains from users (our patients) who are rushed inside a world of unnecessary tests, studies, and procedures that have an excessive, and in most countries, unsustainable cost for the healthcare system.

The irony is that by improving life expectancy we end up having more old patients who, on many occasions, suffer from loneliness and grief. With today’s medical approach, doctors simply cannot bring any remedies to them. Instead, nearness is needed here to examine the natural condition of man and be able to develop our profession fully by offering that lenitive as part of the medical prescription.

Ms. Ellen Trane Nørby, secretary of health in Denmark, one of the highest ranking countries in effective healthcare systems worldwide has said: “Something must be wrong in Denmark when we’re spending 50% of the healthcare budget in the last 90 days of a human life to delay the inevitable in just a few weeks.”2

Abandonment, sadness, and isolation in old patients who live in developed countries generates astronomical costs at the ER when they are actually looking for social support.

An article published on The New York Times3 has brought the program Element Care –non lucrative and for old adults– to everyone’s attention. This program provides those elderly who are eligible with one tablet with a software and a virtual pet that interacts with them, talks to them about sports and pastimes, shows them memories of their lives and, above all, tells them that they are loved.

The patients know that this device is connected to an emerging startup called Care Coach. They also know that the employees who operate this platform see, listen and give remote answers to them, but at the end of the day they come to love their little pet, feeling that they still mean something and that someone else still cares.3

Today’s society is on a non-stop rampage towards progress. We are modernizing consumption without having developed thought first and we are embarked on a technological frenzy that perpetuates itself and turns us into isolated entities that only interact with one another through cybernetic applications. Let us commit ourselves to becoming social individuals back again and humanizing artificial intelligence. Let us be a replica of our ancestors who lived their lives around the fire given to them by the good titan Prometheus.

As physicians I think we should look in the mirror for just a second and ask ourselves whether we are treating patients the same way we would like to be treated. If the answer is no, let’s make hugs last longer than our well-known narcissism.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Harari YN. Sapiens:A brief history of humankind. London:Random House;2014.

2. Maglio P. La dignidad del otro:puentes entre la biología y la biografía. Buenos Aires:Libros del Zorzal;2008.

3. Bowles N. Human Contact Is Now a Luxury Good. The New York Times. 2019. Available online:https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/23/sunday- review/human-contact-luxury-screens.html. Accessed 1 May 2019.

Corresponding author: P.º de las Garzas 12, Isabel Villas, 10504 Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

E-mail address: garcialithgow@gmail.com (C.H. García Lithgow).

The optimal management of chronic anticoagulation is still controversial to this day both in clinical cardiology and particularly in interventional cardiology. The progressive aging of the population has increased exponentially the percentage of patients with an indication for chronic oral anticoagulation who undergo percutaneous invasive procedures to up to 5%-10% of the total. Also, most of them suffer from atrial fibrillation.1

Until the arrival of new direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC), most of these patients were anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists (VKA). Invasive procedures used to be performed after withdrawing oral anticoagulation and using bridging anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin.2 We believe that this widely used strategy in our setting should be put into question though. In the first place, the prothrombotic rebound effect has been reported as associated with the withdraw and reset of VKA.3 Secondly, the interaction of anticoagulants with a different mechanism of action used in patients on bridging therapy can have pro-hemorrhagic and procoagulant consequences. As a matter of fact, the actual clinical guidelines recommend avoiding the concomitant use of unfractionated heparin in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI).4 Also, more hemorrhagic complications associated with bridging therapy have been confirmed in patients treated with invasive or surgical procedures (1.3% vs 3.2%),5 in patients undergoing PCI (8.3% vs 1.7% and 6.8% vs 1.6%7), and in one meta-analysis (odds ratio, 5.40; 95% confidence interval, 3.00-9.74).8 Overall, none of these studies revealed more thromboembolic events associated with the absence of bridging therapy.5-8 With the actual evidence available today, we should ask ourselves why many clinical practice protocols in our setting recommend the use of bridging therapy with VKA and low molecular weight heparin in patients on chronic anticoagulation

There is little evidence from the studies published so far that specifically compare uninterrupted strategies with anticoagulation and interrupted strategies without bridging therapy. We could argue that vascular access is safer if used in uncoagulated patients. However, the PCI is a low-risk of bleeding procedure9 when performed through the access of choice which is the radial access1,4 (used in Spain in up to 90% of the cases).10 Also, yet despite the doubts of many interventional cardiologists, therapeutic warfarin treatment seems to provide sufficient anticoagulation for PCI, and additional heparins are not needed and may increase access site complications.11 Actually this is what the clinical guidelines establish when the international normalized ratio (INR) is above 2.54. In any case, we always have this possibility of adding heparin during the PCI, always bearing in mind that when choosing radial access, the incidence of bleeding is low, and the chances of radial occlusion or thrombosis of the materials drop.

Yet despite the growing use of DOACs in the clinical practice, the evidence available today for its use during the procedure is scarce in patients undergoing PCI. This contrasts with the benefit shown with the use of VKA in revascularized patients who need antiplatelet therapy12 or even as adjuvant therapy for the management of acute coronary syndrome.4 In an article published on REC: Interventional Cardiology, Ramírez Guijarro et al.13 talk about their own initial experience with same-day diagnostic catheterizations without DOAC withdrawal in patients on chronic anticoagulation. It is interesting that no differences were seen in the incidence of hemorrhages or radial occlusions compared to patients without prior antiplatelet therapy or with uninterrupted therapy with VKA. The way we see it, this is a pioneering strategy in our setting which, although it does not validate its use in PCIs with stent implantation, it provides evidence in the right direction. In our opinion, the uninterrupted strategy of anticoagulation when using the radial access has 2 main advantages. The first advantage is the simplification of the procedure for doctors and patients alike especially in outpatient same-day procedures. The benefit of this simplification is potentially higher in patients treated with DOACs since the monitoring of the INR is not necessary at admission and the complexity of withdrawal protocols is avoided based on the half-life of DOACs and renal function. The second advantage is the safety shown with its use since it reduces bleeding complications without improving thromboembolic complications.

In sum, with the evidence available today we know that: a) we should avoid prescribing systematic bridging therapy with low molecular weight heparin in patients undergoing catheterizations/PCI. When dealing with a procedure where there is a high risk of bleeding, the best thing to do is to withdraw anticoagulation without using bridging therapy in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation; b) we should keep VKAs during catheterizations/PCIs performed through radial access; c) stent implantation seems safe with VKA, but heparin can also be prescribed based on the INR and experience; d) diagnostic catheterizations on DOAC therapy seem safe.

In sum, we still need more evidence on this ongoing debate. Studies like the one conducted by Ramírez Guijarro et al.13 are extremely useful but future randomized trials should elucidate what the best antithrombotic strategy is for stent implantation in patients treated with DOAC or VKA. Similarly, clinical guidelines should come to terms on the actual recommendations based on the evidence available today since they do not agree on many issues as table 1 shows. The ultimate goal should be finding the optimal strategy which should be easy to implement, effective, and safe for our patients.

Table 1. Summary of actual anticoagulation recommendations in patients who are going to undergo invasive procedures

| Group | Recommendations for patients treated with VKA | Recommendations for patients treated with DOAC |

|---|---|---|

| ACC 2012 Consensus Document on standards at the cath. lab2 | - Withdraw - INR < 2.2 for radial access | - Always withdraw dabigatran |

| ESC 2015 Guidelines on the management of NSTEACS4 | - Uninterrupted strategy - Without parenteral anticoagulation when INR > 2.5 - Additional dose of parenteral anticoagulation when INR < 2.5 | - Uninterrupted strategy - Always administer additional dose of parenteral anticoagulation (60 IU/kg of UFH) |

| ESC 2017 Guidelines on the management of STEMI14 | - Uninterrupted strategy - Always administer additional parenteral anticoagulation | - Uninterrupted strategy - Always administer additional parenteral anticoagulation |

| ACC 2017 Consensus Document on the management of anticoagulation during the procedure in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation9 | - Uninterrupted strategy without bridging therapy | - Withdraw for 24-96 h - No bridging therapy |

| AHA Position Statement on DOAC therapies15 | - Withdraw for 12-48 h - Consider bridging therapy with heparin in the presence of high embolic risk - Add heparin during the procedure | |

| European EHRA, EAPCI, ACCA Consensus Document 2018 on anticoagulation in patients undergoing interventional procedures1 | - Uninterrupted strategy - Administer 30-50 IU/kg of UFH | -Withdraw for 12-48 h without bridging therapy with elective percutaneous coronary interventions - Administer 70-100 IU/kg of UFH |

|

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACCA, European Association of Acute Cardiac Care; AHA: American Heart Association; DOAC, direct-acting oral anticoagulants; EAPCI, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions; EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; INR, international normalized ratio; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VKA, vitamin K antagonists. |

||

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Lip GYH, Collet JP, Haude M, et al. 2018 Joint European consensus document on the management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous cardiovascular interventions:a joint consensus document of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA). Europace. 2019;21:192-193.

2. Bashore TM, Balter S, Barac A, et al. 2012 American College of Cardiology Foundation/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions expert consensus document on cardiac catheterization laboratory standards update:A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2221-2305.

3. Grip L, Blombäck M, Schulman S. Hypercoagulable state and thromboembolism following warfarin withdrawal in post-myocardial-infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:1225-1233.

4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting Without Persistent ST-segment Elevation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2015;68:1125.

5. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823-833.

6. Lahtela H, Rubboli A, Schlitt A, et al. Heparin bridging vs. uninterrupted oral anticoagulation in patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting. Results from the AFCAS registry. Circ J. 2012;76:1363-1368.

7. Annala AP, Karjalainen PP, Porela P, Nyman K, Ylitalo A, Airaksinen KE. Safety of diagnostic coronary angiography during uninterrupted therapeutic warfarin treatment. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:386-390.

8. Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, Douketis JD, Lim W, Spyropoulos AC. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists:systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates. Circulation. 2012;126:1630-1639.

9. Doherty JU, Gluckman TJ, Hucker WJ, et al. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Periprocedural Management of Anticoagulation in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation:A Report of the American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol.2017;69:871-898.

10. Cid Álvarez AB, Rodríguez Leor O, Moreno R, Pérez de Prado A. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. 27th Official Report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology (1990-2017). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:1036-1046.

11. Kiviniemi T, Karjalainen P, PietiläM, et al. Comparison of additional versus no additional heparin during therapeutic oral anticoagulation in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:30-35.

12. Lopes RD, Heizer G, Aronson R, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndrome or PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1509-1524.

13. Ramírez Guijarro C, Gutiérrez Díez A, Córdoba Soriano JG, et al. Safety profile of outpatient diagnostic catheterization procedures in patients under direct-acting oral anticoagulants. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:161-166.

14. Ibañez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017;70:1082.e1-e61.

15. Raval AN, Cigarroa JE, Chung MK, et al. Management of Patients on Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in the Acute Care and Periprocedural Setting:A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e604-e633.

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Doctor Esquerdo 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain.

E-mail address: elizaga@secardiologia.es (J. Elízaga).

Subcategories

Editorials

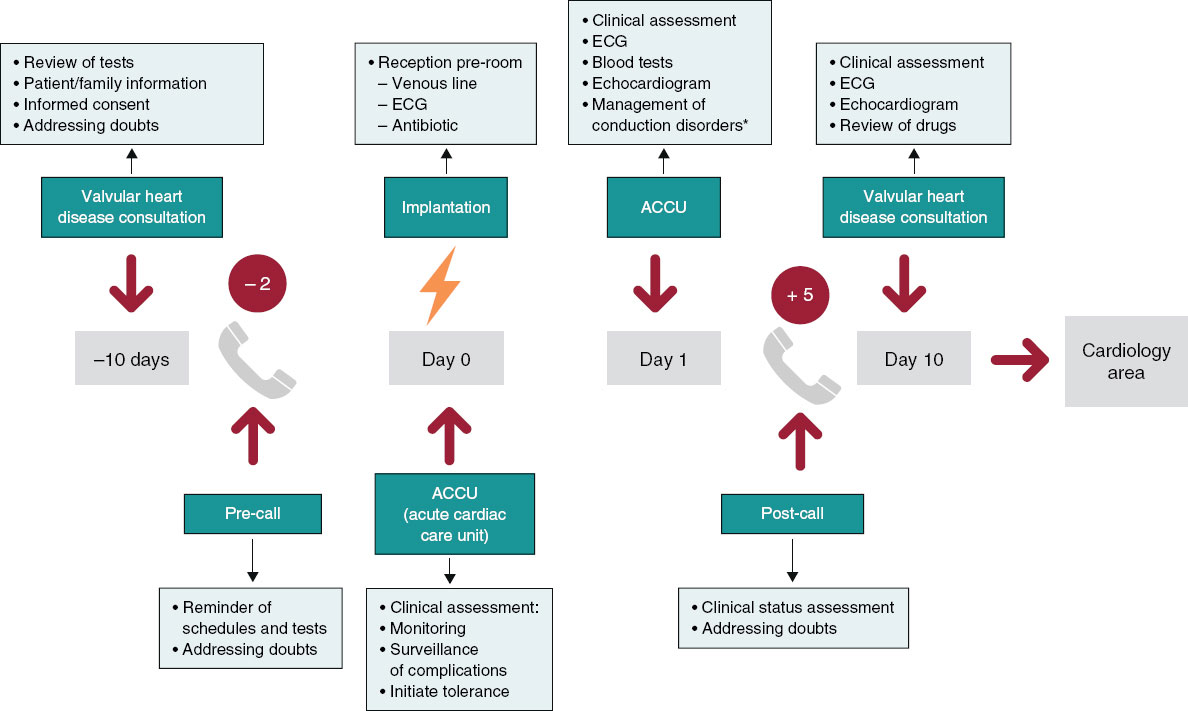

Fast-track TAVI: establishing a new standard of care

Departamento de Cardiología, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain

Original articles

Editorials

All for one or one for all!

Original articles

Congresses abstracts

Debate

Debate: TAVI prosthesis selection for severe calcification

The balloon-expandable technology approach

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, Málaga, Spain

The self-expandable technology approach

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias, Spain