Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

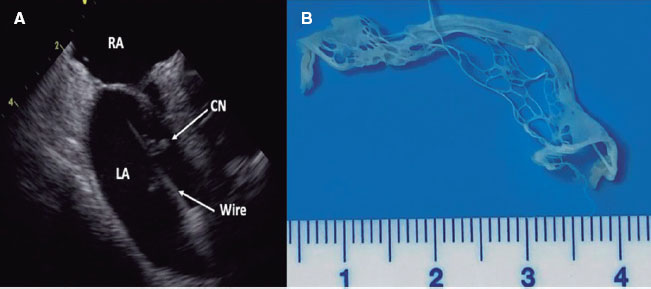

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Contrast-induced-acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is a potential complication of angiographic procedures. The DyeVert Contrast Reduction system (Osprey Medical, United States) is a device to reduce the concentration of contrast medium (CM) in the kidneys by decreasing the amount of CM delivered to patients. Unlike manual systems, few data are available on the DyeVert Power XT system, which is used in conjunction with automated contrast injection. The main aim of our study was to evaluate its effectiveness during percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI).

Methods: Between 2020 and 2022, 101 patients who underwent PCI with the DyeVert Power XT system (case group) were enrolled to evaluate the amount of CM saved through the use of this device, as well as the rate, severity, and predictors of CI-AKI. Patients who underwent PCI without the use of the device (control group) were enrolled to create a matched group allowing assessment of differences in CM and the CI-AKI rate.

Results: : In the case group, the amount of CM saved was 114 ± 42 mL, representing an average of 32% of the total CM. Fourteen patients (13.9%) developed CI-AKI. The only independent predictors of CI-AKI were hematocrit (OR, 0.86; 95%CI, 0.74-0.99; P = .04) and ejection fraction (OR, 0.88; 95%CI, 0.82-0.95; P = .001). As a result of diversion by the device, the amount of CM delivered was lower in the case group than in controls (252 vs 267 mL; P = .42), but this difference was nonsignificant. Equally, the reduction in CI-AKI (14.3% vs 16.3%) was nonsignificant.

Conclusions: Hematocrit and ejection fraction may be more important predictors of CI-AKI than the CM volume normally used during PCI in the general population. The net practical benefit of DyeVert Power XT was low.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury. Contrast media. Percutaneous coronary intervention. DyeVert.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La nefropatía inducida por contraste (NIC) es una potencial complicación de los procedimientos angiográficos. El sistema DyeVert Power (Osprey Medical, Estados Unidos) permite reducir la concentración renal del medio de contraste al disminuir la cantidad administrada a los pacientes. Al contrario que sobre los sistemas manuales, existen pocos datos disponibles sobre el sistema DyeVert, que se utiliza junto a la inyección automática de contraste. El objetivo principal de este estudio fue evaluar su eficacia en procedimientos de intervencionismo coronario percutáneo (ICP).

Métodos: Entre 2020 y 2022 se incluyó a 101 pacientes a quienes se realizó ICP utilizando el sistema DyeVert Power XT (grupo de casos) para evaluar la cantidad ahorrada de medio de contraste, así como la tasa, la gravedad y los predictores de NIC. Además, se seleccionó un grupo control de pacientes a los que se había realizado ICP sin utilizar el sistema DyeVert para comparar la cantidad de medio de contraste administrado y la tasa de NIC.

Resultados: En el grupo de casos se redujo la administración de medio de contraste en 114 ± 42 ml (una media del 32% del total). Desarrollaron NIC 14 pacientes (13,9%). Los predictores de NIC fueron el hematocrito (OR = 0,86; IC95%: 0,74-0,99; p = 0,04) y la fracción de eyección (OR = 0,88; IC95%: 0,82-0,95; p = 0,001). Como resultado de la utilización del sistema DyeVert, la cantidad administrada de medio de contraste fue menor, pero sin diferencias estadísticamente significativas (252 frente a 267 ml; p = 0,42). La tasa de NIC fue menor con el sistema DyeVert, pero sin alcanzar la significación estadística (14,3 frente a 16,3%; p = 1,0).

Conclusiones: El hematocrito y la fracción de eyección, más que la cantidad de contraste administrada, pueden ser predictores de NIC en los pacientes que reciben ICP. El beneficio del sistema DyeVert fue bajo.

Palabras clave: Insuficiencia renal aguda. Medios de contraste. Intervención coronaria percutánea. DyeVert.

Abbreviations

CI-AKI: contrast induced-acute kidney injury. CM/CMV: contrast medium/contrast medium volume. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Contrast induced-acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is a dreaded complication after diagnostic and interventional angiographic procedures and is linked to increased morbidity and mortality. In a large recent meta-analysis, the pooled incidence of CI-AKI after coronary angiography was 12.8%, with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) 11.7%-13.9%, and the associated mortality was 20.2% (95%CI, 10.7%-29.7%).1 Multiple risk factors have been identified: contrast medium volume (CMV), advanced age (> 75 years), diabetes, anemia, conditions associated with hypotension, and ejection fraction (EF) < 40%.2,3 Many of these risk factors are included in the Mehran score,2 which identifies 4 risk classes of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) after PCI: low (≤ 5 points), moderate (6-10 points), high (11-15 points), and very high (≥ 16 points). The Mehran score and the recent Mehran 2 score4 assign 1 point for each 100 mL of CMV up to a dose of 299 mL. Because volume depletion increases the CM concentration in renal tubules, the main preprocedural measure to reduce the occurrence of CI-AKI is intravenous administration of normal saline before and after the procedure, because other solutions provide no benefits5; hydration should be started 12 hours before and continued for 24 hours after the procedure at 1 mL/kg/h or 0.5 mL/kg/h if EF < 35% or New York Heart Association (NYHA) class > 2.6 Another means of decreasing CM concentration in the kidneys is the DyeVert Contrast Reduction system (Osprey Medical Inc, United States), which reduces the amount of CMV delivered to patients during angiographic procedures, with noninferior image quality as attested by independent reviewers.7,8 The DyeVert, DyeVert Plus and DyeVert Plus EZ are used in conjunction with manual contrast injection, and the DyeVert Power XT is used with automated contrast injection; the latter system has been little studied. The main aim of our study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the DyeVert Power XT system in reducing CM delivery during PCI.

METHODS

Study population

This single center, observational study was performed in patients who underwent PCI between September 2020 and December 2022 with the DyeVert Power XT system (case group) and in patients who underwent PCI during a similar period without the use of the device (control group).

Inclusion criteria for both groups were as follows: chronic kidney disease (CKD) [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/m2] and/or need for a complex PCI with the likelihood of receiving a large amount of CM; previous coronary artery bypass graft (CABG); chronic total occlusion (CTO) (complete blockage of a coronary artery lasting at least 3 months); bifurcation; and left main and/or multivessel disease (at least 2 vessels involved).

The exclusion criterion for both groups was the presence of end-stage kidney failure on dialysis treatment. We collected laboratory, instrumental, clinical, and procedural variables in the case and control groups. Definitions of all these variables are reported in table 1, table 2, table 3, and table 4. For the variables included in the Mehran score, we used the same descriptions as those used in the score. eGFR was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) 4-variable equation, left ventricular EF by 2-dimensional echocardiography during hospitalization and before arrival in the catheterization laboratory, and the risk of any post-PCI CIN by the Mehran score. Bifurcation/left main treatment (with single/double stent) consisted of the proximal optimization technique (POT) with kissing balloon inflation and eventually re-POT in all cases. Total CMV represents the volume that would have been delivered if DyeVert had not been used, ie, the sum of CMV delivered to patients and the CMV saved by DyeVert. CM injection flow was 4 and 3 mL/sec for the left and right coronary artery, respectively.

Table 1. Laboratory, instrumental, clinical characteristics, and Mehran score in the overall population and according to incidence of CI-AKI in the case group

| Characteristics | Overall population (n = 101) | No CI-AKI (n = 87) | CI-AKI (n = 14) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory and istrumental characteristics | ||||

| eGFR, mL/min | 51 ± 18 | 52 ± 19 | 45 ± 16 | .18 |

| HCT | 38.6 ± 4.9 | 39.1 ± 4.8 | 35.5 ± 4.8 | .01* |

| EF | 50 [35-55] | 50 [40-55] | 30 [28-36] | < .001* |

| CKD [eGFR < 60 mL/min/ 1.73 m2] | 73 (72.3) | 63 (72.4) | 10 (71.4) | 1 |

| Anemia [male HCT < 39%, female HCT < 36%] | 48 (47.5) | 38 (43.7) | 10 (71.4) | .10 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 74 (68-80) | 73 (67-80) | 75 (74-81) | .09 |

| Age > 75 years | 39 (38.6) | 32 (36.8) | 7 (50) | .52 |

| Male sex | 80 (79.2) | 68 (78.2) | 12 (85.7) | .73 |

| Overweight [body mass index ≥ 25] | 52 (51.5) | 46 (52.9) | 6 (42.9) | .68 |

| Hypertension | 78 (77.2) | 70 (80.5) | 8 (57.1) | .08 |

| Diabetes | 48 (47.5) | 40 (46) | 8 (57.1) | .62 |

| Dyslipidemia | 68 (67.3) | 57 (66) | 11 (79) | .51 |

| Current smoker | 24 (23.8) | 20 (23) | 4 (28.6) | .74 |

| Former smoker | 35 (34.7) | 32 (36.8) | 3 (21.4) | .37 |

| CHF [NYHA class ≥ 3 and/or history of pulmonary edema] | 37 (36.6) | 25 (28.7) | 12 (85.7) | < .001* |

| Acute coronary syndrome presentation | 38 (37.6) | 31 (35.6) | 7 (50) | .46 |

| Hypotension [Systolic arterial pressure < 80 mmHg for ≥ 1 h requiring inotrope] | 4 (4) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (14.3) | .09 |

| Mehran score | ||||

| Mehran CI-AKI risk class: | ||||

| Low | 24 (23.8) | 24 (27.6) | 0 (0) | .04* |

| Moderate | 26 (25.7) | 24 (27.6) | 2 (14.3) | .51 |

| High | 34 (33.7) | 29 (33.3) | 5 (35.7) | 1 |

| Very high | 17 (16.8) | 10 (11.5) | 7 (50) | .002* |

| Mehran score, points | 11 ± 5 | 10 ± 5 | 15 ± 4 | < .001* |

|

Values are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [first quartile-third quartile]. *Statistically significant P-value (P < .05). CHF, congestive heart failure; CI-AKI, contrast induced-acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HCT, hematocrit; NYHA, New York Heart Association. |

||||

Table 2. Procedural characteristics in the overall population and according to incidence of CI-AKI in the case group

| Characteristics | Overall population (n = 101) | No CI-AKI (n = 87) | CI-AKI (n = 14) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural characteristics (angiography/PCI complexity/complications) | ||||

| Previous CABG | 20 (19.8) | 18 (20.7) | 2 (14.3) | .73 |

| CTO [complete blockage of a coronary artery lasting at least 3 months] | 12 (11.9) | 11 (12.6) | 1 (7.1) | 1 |

| No. vessels treated in the same procedure: | ||||

| 1 | 57 (56.4) | 52 (59.8) | 5 (35.7) | .09 |

| 2 | 40 (39.6) | 32 (36.8) | 8 (57.1) | .15 |

| 3 | 4 (4) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | .45 |

| No. bifurcations treated in the same procedure: | ||||

| 0 | 67 (66.3) | 58 (66.7) | 9 (64.3) | 1 |

| 1 | 31 (30.7) | 27 (31) | 4 (28.6) | 1 |

| 2 | 3 (3) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (7.1) | .36 |

| Left main treatment | 25 (24.8) | 20 (23) | 5 (35.7) | .33 |

| Stent, number | 2 [1-3] | 2 [1-3] | 2 [1-3] | .75 |

| Stent lenght, mm | 52 [31-88] | 51 [30-91] | 57 [36-73] | .95 |

| Perforation | 3 (3) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| IABP use | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | .14 |

| Rotablator use | 3 (3) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (14.3) | .05 |

| Procedural characteristics (others) | ||||

| Radial access | 88 (87.1) | 75 (86.2) | 13 (92.9) | .69 |

| Femoral access | 27 (26.7) | 21 (24.1) | 6 (42.9) | .19 |

| Operator | ||||

| L | 52 (51.5) | 47 (54) | 5 (35.7) | .20 |

| A | 30 (29.7) | 26 (29.9) | 4 (28.6) | 1 |

| B | 4 (4) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | .46 |

| V | 13 (12.9) | 10 (11.5) | 3 (21.4) | .38 |

| S | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (7.1) | .26 |

| Contrast medium type: | ||||

| Iomeprol 350 | 9 (8.9) | 7 (8) | 2 (14.3) | .61 |

| Iohexol 350 | 13 (12.9) | 11 (12.6) | 2 (14.3) | 1 |

| Iodixanol 320 | 79 (78.2) | 69 (79.3) | 10 (71.4) | .50 |

| Contrast medium dose delivered, mL | 242 [189-300] | 240 [188-306] | 258 [195-277] | .95 |

| Total contrast medium dose [delivered plus saved], mL | 355 ± 110 | 354 ± 79 | 356 ± 106 | .95 |

| IVUS use | 24 (23.8) | 23 (26.4) | 1 (7.1) | .18 |

|

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [first quartile-third quartile]. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI-AKI, contrast induced-acute kidney injury; CTO, chronic total occlusion; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound. |

||||

Table 3. Laboratory, instrumental, clinical characteristics, and Mehran score of cases and controls in the matched group

| Characteristics | No DyeVert (n = 49) | DyeVert (n = 49) | P | Standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory and istrumental characteristics | ||||

| eGFR, mL/min | 53 ± 18 | 51 ± 18 | .70 | 0.11 |

| HCT | 37.8 ± 4.1 | 38.2 ± 4.9 | .68 | 0.08 |

| EF | 50 [40-55] | 50 [35-55] | .68 | 0.13 |

| CKD [eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2] | 36 (73.5) | 34 (69.4) | .82 | 0.09 |

| Anemia [male HCT < 39, Female HCT < 36] | 27 (55.1) | 24 (49) | .69 | 0.12 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 75 ± 9 | 75 ± 9 | .96 | 0.01 |

| Age > 75 years | 26 (53.1) | 24 (49) | .84 | 0.08 |

| Male sex | 38 (77.6) | 41 (83.7) | .61 | 0.15 |

| Overweight [body mass index ≥ 25] | 22 (44.9) | 24 (49) | .84 | 0.08 |

| Hypertension | 33 (67.3) | 37 (75.5) | .50 | 0.19 |

| Diabetes | 19 (38.8) | 20 (40.8) | 1 | 0.04 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 (57.1) | 32 (65.3) | .53 | 0.17 |

| Current smoker | 11 (22.4) | 10 (20.4) | 1 | 0.05 |

| Former smoker | 16 (32.7) | 18 (36.7) | .83 | 0.09 |

| CHF [NYHA class ≥ 3 and/or history of pulmonary edema] | 15 (30.6) | 15 (30.6) | 1 | < 0.01 |

| Acute coronary syndrome presentation | 27 (55.1) | 25 (51) | .84 | 0.08 |

| Hypotension [systolic pressure < 80 mmHg for ≥ 1 h requiring inotrope] | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.1) | 1 | < 0.01 |

| Mehran score | ||||

| Mehran CI-AKI risk class: | ||||

| Low | 12 (24.5) | 10 (20.4) | .63 | 0.09 |

| Moderate | 12 (24.5) | 15 (30.6) | .50 | 0.14 |

| High | 13 (26.5) | 15 (30.6) | .65 | 0.09 |

| Very high | 12 (24.5) | 9 (18.4) | .46 | 0.16 |

| Mehran score, points | 11 ± 6 | 11 ± 6 | .86 | 0.04 |

|

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [first quartile-third quartile]. CHF, congestive heart failure; CI-AKI, contrast induced-acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HCT, hematocrit; NYHA, New York Heart Association. |

||||

Table 4. Procedural characteristics of cases and controls in the matched group

| Characteristics | No DyeVert (n = 49) | DyeVert (n = 49) | P | Standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural characteristics (angiography/PCI complexity/complications) | ||||

| Previous CABG | 8 (16.3) | 6 (12.2) | .56 | 0.10 |

| CTO [complete blockage of a coronary artery lasting at least 3 months] | 6 (12.2) | 8 (16.3) | .77 | 0.13 |

| No. vessels treated in the same procedure: | ||||

| 1 | 32 (65.3) | 29 (59.2) | .53 | 0.12 |

| 2 | 15 (30.6) | 17 (34.7) | .67 | 0.08 |

| 3 | 2 (4.1) | 3 (6.1) | 1 | 0.10 |

| No. bifurcations treated in the same procedure: | ||||

| 0 | 33 (67.3) | 31 (63.3) | .67 | 0.09 |

| 1 | 15 (30.6) | 16 (32.7) | .83 | 0.04 |

| 2 | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4) | 1 | 0.12 |

| Left main treatment | 12 (24.5) | 13 (26.5) | 1 | 0.05 |

| Stent, number | 2 [1-3] | 2 [1-3] | .30 | 0.15 |

| Stent lenght, mm | 46 [30-85] | 52 [33-97] | .41 | 0.13 |

| Perforation | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2) | 1 | 0.12 |

| IABP use | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 | 0.20 |

| Rotablator use | 0 (0) | 2 (4.1) | .49 | 0.24 |

| Procedural characteristics (others) | ||||

| Radial access | 41 (83.7) | 45 (91.8) | .35 | 0.24 |

| Femoral access | 11 (22.4) | 15 (30.6) | .49 | 0.18 |

| Operator: | ||||

| L | 24 (49) | 24 (49) | 1 | < 0.01 |

| A | 17 (34.7) | 17 (34.7) | 1 | < 0.01 |

| B | 5 (10.2) | 3 (6.1) | .71 | 0.20 |

| V | 3 (6.1) | 5 (10.2) | .71 | 0.12 |

| Contrast medium type: | ||||

| Iomeprol 350 | 7 (14.3) | 4 (8.2) | .34 | 0.21 |

| Iohexol 350 | 9 (18.4) | 10 (20.4) | .80 | 0.06 |

| Iodixanol 320 | 33 (67.3) | 35 (71.4) | .66 | 0.10 |

| IVUS use | 10 (20.4) | 11 (22.4) | 1 | 0.05 |

|

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [first quartile-third quartile]. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI-AKI, contrast induced-acute kidney injury; CTO, chronic total occlusion; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound. |

||||

Image quality was evaluated by operators during the procedures. When quality was inadequate, exclusion of the device from the CM line was allowed for the shortest possible time.

AKI was defined as a rise in the concentration of serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours after CM administration from the baseline value obtained before CM injection; further measurements after 48 hours were collected in patients with worsening kidney function; for its prevention, all patients received hydration with sodium chloride 0.9% intravenous solution at a rate of 1 or 0.5 mL/kg/h, as appropriate. The severity of AKI was defined according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) stages.

The research reported was performed in accordance with recommendations for clinical investigation (Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association, October 2013) and was approved by an ethics committee. We declare that relevant informed consent was obtained from all participants and is available.

Objectives

In the case group, we evaluated the following: a) the amount of CMV saved using DyeVert and image quality; b) the rate and severity of CI-AKI and the rate of in-hospital all-cause death; c) laboratory, instrumental, clinical, and procedural differences in the 2 subgroups defined on the basis of the incidence of AKI; and d) independent predictors of CI-AKI.

In the overall population of the case and control groups, we performed propensity score matching (PSM) to obtain a group of patients with a sufficiently good balance (matched group), in which we evaluated the following: a) differences in CMV, and b) rate and severity of CI-AKI.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as the number and percentage of patients. Continuous parametric data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation and continuous nonparametric data as the median [lower and upper quartile]; for assessment of normality, the Kolmogorov test was used. Patients’ categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test (with Yates’ correction for continuity in the case of variables with only 2 categories) or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. The unpaired t-test was used for continuous parametric variables and the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous nonparametric variables; the same tests were used in the matched group. On univariate analysis, significance was defined as P < .05. To establish the independent predictors of AKI, we performed multivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables were selected according to significance in the univariate analysis. The chosen method was stepwise backward regression with a maximum of 20 iterations. Multicollinearity was assessed with tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to establish the optimal cutoffs of independent predictors for the diagnosis of AKI. To perform PSM, the algorithm used was nearest neighbor matching 1:1 with a caliper size of ± 0.2. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, release 29, with R 4.2 implementation to perform PSM.

RESULTS

Analysis in the case group

A total of 101 patients (median age 74 [68-80] years, male sex 79.2%, CKD 72.3%) underwent PCI with the use of the DyeVert Power XT system.

In the overall population of the case group, mean hematocrit (HCT) was 38.6 ± 4.9 %, median EF was 50% [35%-55%], and mean Mehran score was 11 ± 5 points.

Congestive heart failure (CHF) was present in 37 patients (36.6%), Mehran CI-AKI very high-risk class was present in 17 patients (16.8%) and Mehran CI-AKI low-risk class was present in 24 patients (23.8%) (table 1).

We enrolled 20 patients (19.8%) with previous CABG, 12 (11.9%) with CTO, 34 (33.7%) with bifurcations, 25 (24.8%) with left main coronary artery disease, and 44 (43.6%) with multivessel disease. Delivered CM was 242 (189-300) mL, total CM was 355 ± 110 mL, and saved CM was 114 ± 42 mL, with an average of 32% of the total CMV (table 2). In almost all patients (n = 96, 95% of patients), image quality was adequate, while the device was excluded to make it adequate for the shortest possible time in 5 patients. Without these exclusions, saved CMV would have been slightly higher and with trivial changes with regard to the comparison with controls: 33% of the total, a value derived from patients without exclusions (n = 96).

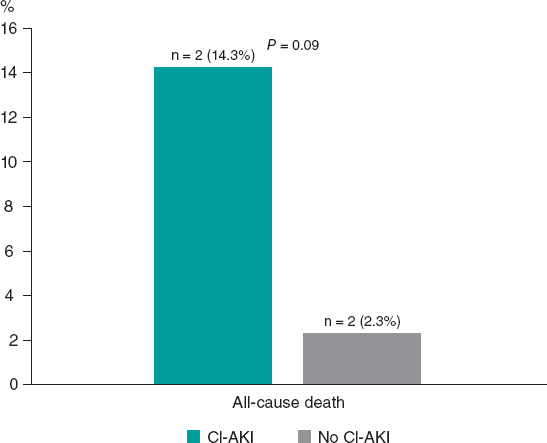

A total of 14 (13.9%) patients developed CI-AKI (AKI-KDIGO 1, 2, 3: 6.9%, 3%, and 4%, respectively). The results of the univariate analysis for the overall population and according to the incidence of CI-AKI in the case group are reported in table 1, table 2, and figure 1.

Figure 1. In-hospital all-cause mortality rate according to onset of CI-AKI in the case group. CI-AKI, contrast induced-acute kidney injury.

Compared with patients not developing CI-AKI, those in the CI-AKI subgroup had lower HCT values (35.5 ± 4.8 vs 39.1 ± 4.8; P = .01), lower EF values (30 [28-36] vs 50 [40-55]; P < .001) and higher Mehran score values (15 ± 4 vs 10 ± 5; P < .001).

In addition, the first patients more frequently had CHF [12 (85.7%) vs 25 (28.7%); P <.001] and Mehran CI-AKI very high-risk class (7 [50%] vs 10 [11.5%]; P =.002) and less frequently had Mehran CI-AKI low-risk class (0 [0%] vs 24 [27.6%]; P = .04).

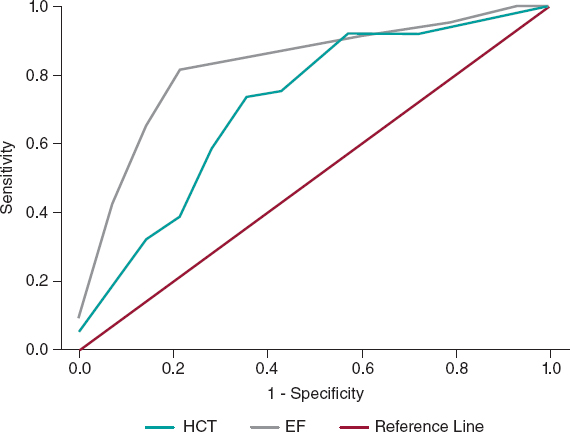

No significant differences were found in the remaining laboratory, instrumental, or clinical features or the procedural variables between the 2 subgroups; in particular, CM was slightly higher in CI-AKI patients: 258 [195-277] vs 240 [188-306] mL, total 356 ± 106 vs 354 ± 79 mL; P = .95 for both variables delivered. In the multivariate analyses, independent predictors of CI-AKI were HCT (OR, 0.86, 95%CI, 0.74-0.99; P = .04) and EF (OR, 0.88, 95%CI, 0.82-0.95; P = .001); the percentage accuracy in classification of the model was 88%, while tolerance and VIF values (0.99 and 1.01, respectively) showed no multicollinearity. The HCT ROC curve showed the following values: area under curve (AUC) 0.71 with 95%CI 0.56-0.87; P = .01; a cutoff of 36.3% had the best sensitivity (72%) and specificity (71%) for the outcome (figure 2). The EF ROC curve showed the following values: AUC 0.83 with 95%CI 0.72-0.94; P = .001; a cutoff of 37% had the best sensitivity (82%) and specificity (79%) (figure 2); therefore, our best predictor was EF < 40%.

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic curves showing the diagnostic ability of HCT and EF for the diagnosis of CI-AKI in the case group. CI-AKI, contrast induced-acute kidney injury; EF, ejection fraction; HCT, hematocrit.

There were 4 in-hospital all-cause deaths overall, 2 deaths in each subgroup (CI-AKI and no–CI-AKI subgroups), as shown in figure 1.

Analysis in the matched group

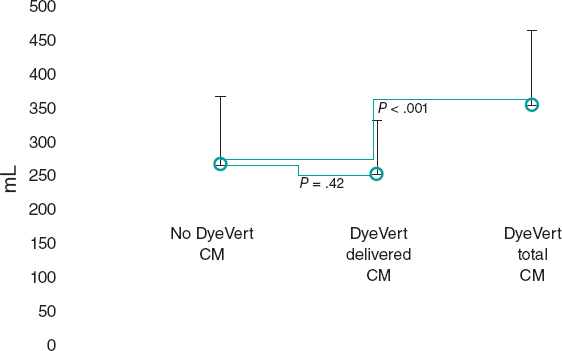

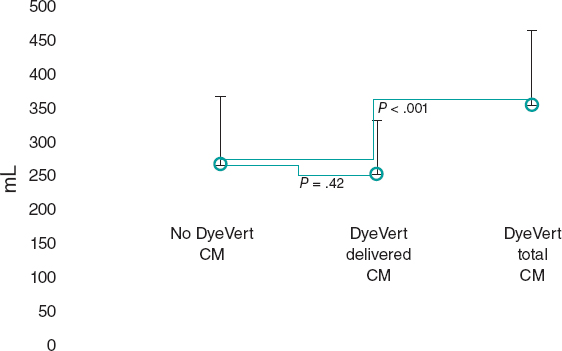

After the matching process, 49 patients remained in the control (no DyeVert) and case (DyeVert) groups with no significant imbalance (ie, standardized mean differences < ± 0.25), as reported in table 3 and table 4. As shown in figure 3, delivered CM was slightly lower in the DyeVert group than in the no-DyeVert group, with no significant difference (252 ± 80 vs 267 ± 101 mL; P = .42), while total CM was significantly higher in the DyeVert group (354 ± 110 vs 267 ± 101 mL; P < .001). The CI-AKI rate was slightly lower in the case group than in the control group (14.3% vs 16.3%; P = .99) with slightly more advanced stages of AKI in controls (table 1 of the supplementary data), without significance.

Figure 3. Contrast medium in cases and controls in the matched group. CM, contrast medium; blue dots represent the median values; vertical black lines represent the standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

In the case group, the DyeVert Power XT system saved 32% of CM and image quality was adequate in almost all cases; the only independent predictors of CI-AKI were HCT and EF.

In the matched group, total CM was higher in cases than in controls. After diversion by the device, delivered CM was slightly lower in cases than in controls, but without significance. The reduction in CI-AKI was also nonsignificant.

The DyeVert system is a second-generation device to reduce the amount of CM delivered to patients during angiographic procedures. The first generation was the AVERT system (Osprey Medical Inc), which showed a relative reduction of approximately 23% in CMV among PCI patients compared with controls; the use of the device did not reduce the AKI rate.9 DyeVert Power XT is used in combination with automatic injection; few data are available in this context, being limited to 2 studies that investigated 2610 and 9 patients,11 without a control group. There are more data on manual injection (1696 patients, 15 studies); all these 17 studies were collectively analyzed in the meta-analysis by Tarantini et al.12

In that meta-analysis, the mean saved CMV in the DyeVert group was reported by 7 observational studies and ranged from 34% to 47% of total CMV; the pooled estimate value was approximately 39.5% using manual CM injection systems; of note, the lowest value (34%) was achieved using DyeVert Power XT. We found a similar value in the DyeVert (case) group. These reduced values compared with manual systems may be related to different pressures generated during automatic contrast injection.

In our case group analysis, CMV was not significantly correlated with the occurrence of CI-AKI, which instead was independently predicted by lower HCT and EF values, which are known risk factors, as shown by Mehran scores.2,4 EF was also an independent predictor in the study by Briguori et al.13 Our findings confirm the importance of first identifying the variables (eg, those in the Mehran or Mehran 2 scores)2,4 that classify patients at higher risk of CI-AKI to apply appropriate preventive strategies. In the present study, these patients were identified by HCT and EF and consequently the latter variables (especially EF) may be more important predictors than CMV, which is normally used during PCI in the general population. In the above-mentioned scores, CMV was also an independent predictor of CI-AKI and, consequently, using the smallest possible value of CMV is still important, especially in higher risk patients. DyeVert thus has the potential benefit of reducing CIN, depending on its efficacy compared with controls, which was evaluated in the above-mentioned meta-analysis and in the present study.

In the meta-analysis, approximately half of the studies included controls for comparison. Delivered CM was usually lower in DyeVert patients than in controls. In these cases, the difference ranged from 22 to 50 mL,12 with the highest differences being reported in the studies by Tajti et al. (200 [153-256] vs 250 [170-303] mL; P = .04) and Briguori et al. (99 ± 50 vs 130 ± 50 mL; P <.001).13,14 Delivered CMV was slightly higher (difference of 2 mL) in the DyeVert group only in the study by Bunney et al.15 The pooled analysis showed a significant decrease in delivered CMV with DyeVert use relative to the control group. Of note, details about prior CABG, CTO and left main treatment were reported only in 1 work14 and the number of vessels treated was reported only in another work.13 The treatment of bifurcations and differences in operators were not reported. All these procedural characteristics, which may influence the amount of CM delivered during PCI, were included in our study and we used a matched group with a sufficiently good balance in the studied characteristics.

In our matched group, delivered CM was lower in the case group than in the control group, but the difference was slight and nonsignificant, while total CM (also called attempted in the meta-analysis) was significantly higher in the case group than in the control group. Consequently, the net practical benefit of the device in terms of spared CM was low. In our work, procedural characteristics (eg, procedural complexity), which could cause discrepancies in CM injections, were balanced in the matched group. Based on these findings, we believe that the control group required more prolonged and/or a greater number of contrast injections (and consequently more total CM) to achieve adequate image quality. In previous studies, adequate image quality was achieved with DyeVert in 98% of cases,12 a value similar to ours, but those studies did not discuss the need for prolonged injections and more total CM compared with controls to maintain image quality when DyeVert is used. Few data are available on total CM, but previous studies reporting this information indicate that total CM was higher in DyeVert patients than in controls (Briguori et al., P-value almost significant; Kutschman et al., P-value not reported).12,13,16

The reduction in CI-AKI in the present study was not statistically significant. In the meta-analysis, the pooled relative risk for CI-AKI associated with DyeVert system use was 0.60 (95%CI, 0.40-0.90; P = .01), which was a result derived from 5 studies. Moreover, in a recent abstract not included in the meta-analysis, postprocedure eGFR values among patients undergoing coronary and/or peripheral angiography were significantly more stable in the DyeVert group than in controls.17

Analysis of the 5 above-mentioned studies separately revealed that our results are mainly in agreement; indeed, the relative risk was significantly lower in only 1 study in the nonpooled analysis.13

The type of CM was not associated with the occurrence of CI-AKI; as recommended,18 we used iso-osmolar (Iodixanol 320) or low-osmolar (Iomeprol 350 or Iohexol 350) contrast agents to prevent CIN. Given the presence of more favorable evidence,19 we preferred to use the iso-osmolar agent and reserved the other agents to low-risk patients.

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. Second, the study design was single center, observational and retrospective, although we performed PSM to reduce potential confounding bias. Third, we excluded patients not meeting the inclusion criteria, as they were usually at low risk of CI-AKI. Therefore, our results should be generalized with caution, since the analyzed patients may be not representative of the general population. In this work the variable of sex has not been taken into account in accordance with the SAGER guidelines.

CONCLUSIONS

The DyeVert Power XT system saved 32% of CM, but only HCT and EF were independent predictors of CI-AKI and the main predictor was EF < 40%. Therefore, these variables (especially EF) may be more important than CMV, which is normally used during PCI in the general population.

PCI with this system required more total CM compared with that in controls to achieve adequate image quality. Consequently, after CM saving by the device, delivered CM was only slightly lower than CM in controls (mean difference of 15 mL) and this difference was nonsignificant. Therefore, the net practical benefit of the system was low. Equally, the reduction in CI-AKI (14.3% vs 16.3%) was not statistically significant.

Future studies are needed to confirm these results.

FUNDING

The authors did not receive any grants for this research.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The work has been approved by an Ethics Committee/institution. Informed consent of patients was obtained and archived for the publication of their cases. In this work the variable of sex has not been taken into account in accordance with the SAGER guidelines.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

We didn’t use artificial intelligence for the development of our work.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

F. Vergni, M.Arioti, and M.Leoncini contributed to the design of the work. F. Vergni, M. Arioti, V. Boasi, F.A. Sánchez, M.Leoncini, and F. Ferrari contributed to the acquisition of data. F. Vergni analyzed the data. F. Vergni, M.Arioti, V. Boasi, F.A. Sánchez, M. Leoncini, and F. Ferrari contributed to the interpretation of the data. F. Vergni and M.Arioti contributed to the drafting of the work. F. Vergni, M. Arioti, V. Boasi, F.A. Sánchez, M.Leoncini, and F. Ferrari revised the work and approved the final version to be published.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

What is known about the topic?

- The DyeVert Power XT system (which is used in conjunction with automated contrast injection) has been assessed in only 2 studies, which included a total of 35 patients investigated without a control group and mainly not during PCI.

What does this study add?

- Our study investigated the device in a larger population (n = 101) and during PCI. Moreover, we included a control group and performed propensity score matching to obtain a group of patients with a sufficiently good balance regarding laboratory, instrumental, clinical and procedural characteristics; in addition, among the latter features, we included the treatment of coronary bifurcations and differences between operators, which were not reported in previous studies. The above-mentioned characteristics may influence the outcome (ie, CI-AKI occurrence) and/or the volume of CM used and therefore their inclusion is important when assessing a device to spare CM.

REFERENCES

1. Lun Z, Liu L, Chen G, et al. The global incidence and mortality of contrast-associated acute kidney injury following coronary angiography:a meta-analysis of 1.2 million patients. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1479-1489.

2. Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention:development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393-1399.

3. Azzalini L, Spagnoli V, Ly HQ. Contrast-induced nephropathy:from pathophysiology to preventive strategies. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:247-255.

4. Mehran R, Owen R, Chiarito M, et al. A contemporary simple risk score for prediction of contrast-associated acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention:derivation and validation from an observational registry. Lancet. 2021;398:1974-1983.

5. Almendarez M, Gurm HS, Mariani J Jr, et al. Procedural strategies to reduce the incidence of contrast-induced acute kidney injury during percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1877-1888.

6. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

7. Desch S, Fuernau G, Pöss J, et al. Impact of a novel contrast reduction system on contrast savings in coronary angiography –the DyeVert randomised controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:50-53.

8. Zimin VN, Jones MR, Richmond IT, et al. A feasibility study of the DyeVerttm plus contrast reduction system to reduce contrast media volumes in percutaneous coronary procedures using optical coherence tomography. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;30:40-46.

9. Mehran R, Faggioni M, Chandrasekhar J, et al. Effect of a contrast modulation system on contrast media use and the rate of acute kidney injury after coronary angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1601-1610.

10. Amoroso G, Christian J, Christopher A. First European experience using a novel contrast reduction system during coronary angiography with automated contrast injection. [Abstract]. Eurointervention. 2020;16(Suppl. AC):Euro20A-POS426.

11. Bruno RR, Nia AM, Wolff G, et al. Early clinical experiences with a novel contrast volume reduction system during invasive coronary angiography. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;23:100377.

12. Tarantini G, Prasad A, Rathore S, et al. DyeVert Contrast Reduction System Use in Patients Undergoing Coronary and/or Peripheral Angiography:A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:841876.

13. Briguori C, Golino M, Porchetta N, et al. Impact of a contrast media volume control device on acute kidney injury rate in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:76-84.

14. Tajti P, Xenogiannis I, Hall A, et al. Use of the DyeVert system in chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2019;31:253-299.

15. Bunney R, Saenger E, Shah C, et al. Contemporary use of contrast dye reduction technology in a tertiary academic hospital:patient characteristics and acute kidney injury outcomes following percutaneous coronary interventions. In:Acc 2019. 1st Quality Summit;2019 March 13-15;New Orleans, United States.

16. Kutschman R, Davison L, Beyer J. Comprehensive clinical quality initiative for reducing acute kidney injury in at-risk patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiogram and/or percutaneous coronary interventions. In:Scai 2019. 42nd Scientific Sessions;2019 May 19-22;Las Vegas, United States.

17. Olubowale O, Ur Rahman E, U Okoro K, et al. The DyeVert contrast reduction system and contrast induced nephropathy:is it any better?J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(Suppl 9):S903.

18. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

19. Zhao F, Lei R, Yang SK, et al. Comparative effect of iso-osmolar versus low-osmolar contrast media on the incidence of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in diabetic patients:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Imaging. 2019;19:38.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Vergni95@gmail.com (F. Vergni).

ABSTRACT

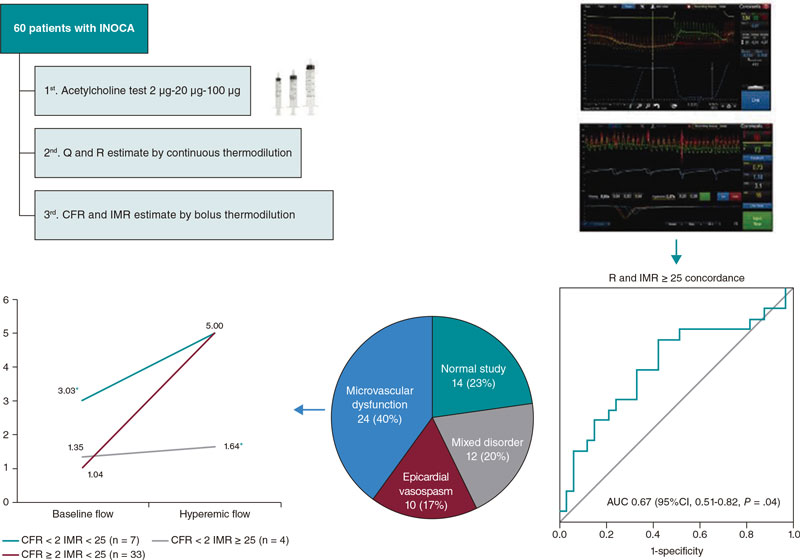

Introduction and objectives: Invasive diagnosis of vasoreactivity and microvascular function may be useful to optimize the management of patients with signs and/or symptoms of myocardial ischemia in the absence of significant coronary stenosis (INOCA). We analyzed the prevalence of the different endotypes, as well as the concordance between 2 diagnostic methods based on thermodilution assessment.

Methods: We prospectively included 60 patients with INOCA who underwent a vasoreactivity test with intracoronary acetylcholine, and measurement of absolute coronary blood flow (Q) and minimum microvascular resistance (R) using continuous thermodilution assessment. Finally, calculations of the coronary flow reserve (CFR) and index of microcirculatory resistance index (IMR) were made using the bolus thermodilution method considering CFR < 2 and MRI ≥ 25 as established pathological cut-off values.

Results: The invasive functional diagnostic procedure allowed patients to be categorized into 4 subgroups: microvascular dysfunction (40%), epicardial vasospasm (17%), mixed disorder (20%), and normal study (23%). No correlation was seen between the Q and the CFR. Using ROC curves, an R > 435 UW was estimated as the optimal cut-off value to identify patients with IMR ≥ 25 with an area under the curve of 0.67 (95%CI, 0.51-0.82; P = .04).

Conclusions: The invasive study of vasoreactivity and microcirculation was feasible and safe. Prevalence of vasospasm and microvascular dysfunction in patients with INOCA was high. The CFR/MRI/Q combined study allowed us to unmask a subtype of microvascular dysfunction characterized by an abnormally high coronary flow at baseline. The concordance seen between the microvascular resistance obtained by continuous thermodilution measurements and the reference method was low so future studies are justified to determine the usefulness of this technique.

Keywords: Microvascular dysfunction. Vasospasm. Acetylcholine. Continuous thermodilution measurements. Microvascular resistance. INOCA.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El diagnóstico invasivo de la vasorreactividad y la función microvascular puede resultar de utilidad para optimizar el manejo de los pacientes con signos o síntomas de isquemia miocárdica en ausencia de estenosis coronarias significativas (INOCA). Se analizó la prevalencia de los distintos endotipos y la concordancia entre 2 métodos diagnósticos basados en la termodilución.

Métodos: Se incluyeron de forma prospectiva 60 pacientes con INOCA a quienes se realizó un test de vasorreactividad con acetilcolina intracoronaria, medida del flujo absoluto (Q) y la resistencia microvascular mínima (R) por termodilución continua y, por último, se calcularon la reserva de flujo coronario (RFC) y el índice de resistencia microvascular (IRM) por termodilución con bolos. Se consideraron como patológicos los puntos de corte establecidos de RFC < 2 e IRM ≥ 25.

Resultados: El procedimiento diagnóstico funcional invasivo permitió clasificar a los pacientes en 4 subgrupos: disfunción microvascular (40%), vasoespasmo epicárdico (17%), trastorno mixto (20%) y estudio normal (23%). No se observó correlación entre Q y RFC. Mediante curvas ROC se estimó una R > 435 UW como el punto de corte óptimo para identificar pacientes con IRM ≥ 25, con un área bajo la curva de 0,67 (IC95%, 0,51-0,82; p = 0,04).

Conclusiones: El estudio invasivo de la vasorreactividad y la microcirculación fue factible y seguro. La prevalencia de vasoespasmo y de disfunción microvascular en pacientes con INOCA fue elevada. El análisis conjunto de RFC, IRM y Q permitió desenmascarar un subtipo de disfunción microvascular caracterizado por un flujo coronario basal anormalmente elevado. La concordancia entre la resistencia microvascular obtenida por termodilución continua respecto al método de referencia fue baja, por lo que se requieren futuros estudios para determinar la utilidad de esta técnica.

Palabras clave: Disfunción microvascular. Vasoespasmo. Acetilcolina. Termodilución continua. Resistencia microvascular. INOCA.

Abbreviations

CFR: coronary flow reserve; INOCA: ischemia with nonobstructive coronary artery disease; IMR: index of microcirculatory resistance; Q: absolute coronary blood flow; R: coronary microvascular resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few years, the term INOCA (ischemia with nonobstructive coronary arteries) has established to define patients with signs or symptoms of ischemic heart disease without angiographically significant obstructive coronary artery disease.1 In these patients, coronary microvascular or epicardial vessel dysfunction could be the pathophysiological mechanism triggering the symptoms and ischemic impairment.2

Currently, the invasive study of microvascular function in patients with INOCA is a recommendation IIa according to the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology.3 What it does is measure the parameters that show its functional or structural status like coronary flow reserve (CFR) or index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR).4

Recently, the possibility of measuring absolute coronary blood flow (Q) and microvascular resistance (R) by continuous thermodilution with the infusion of a physiological saline solution through a specific coronary microcatheter has been described. This technique has potential advantages like its independence from the operator or not needing pharmacologically induced hyperemia.5

The objective of this study is to estimate the prevalence of the different endotypes of patients with INOCA and analyze the correlation between the measurements obtained by continuous thermodilution and the traditional method of intracoronary boluses of physiological saline solutions.

METHODS

This was a prospective and consecutive study of 60 referred patients due to symptoms or signs of myocardial ischemia without angiographically significant coronary artery stenosis on the visual estimate (< 50%) or after functional assessment (resting full-cycle ratio [RFR] > 0.89 or fractional flow reserve [FFR] > 0.80). Severe valvular heart disease, acute coronary syndrome, decompensated heart failure, and any clinical or anatomical condition where the study of microcirculation and vasoreactivity would be considered unnecessary were excluded.

All microcirculation and vasoreactivity studies were scheduled and second-staged. Nitrates and calcium antagonists were withdrawn prior to conducting the tests.

The coronary angiography was performed based on the routine clinical practice via radial access. A spasmolytic cocktail of 200 µg of nitroglycerin was administered. The target artery was the left main coronary artery.

The study was approved by the center ethics research committee and the patients’ written informed consent was obtained.

Vasoreactivity test

First, the vasoreactivity test was performed. Patient monitoring included precordial leads, and baseline angiograms were performed using 2 different projections. The sequential administration of acetylcholine was followed by increasing doses of 2 µg, 20 µg, and 100 µg in intracoronary bolus for 2 min. In the presence of significant bradycardia, the injection was interrupted, and if considered appropriate, it was re-administered at a slower rate. A follow-up angiogram was performed after every dose. In the presence of severe symptoms, changes to the echocardiogram or epicardial spasm 200 µg of intracoronary nitroglycerin were administered.

The test was considered positive based on the criteria established by the COVADIS (Coronary vasomotor disorders international study) group: epicardial spasm in the presence of chest pain, changes to the echocardiogram, and constriction ≥ 90%, and microvascular spasm in the presence of chest pain, and changes to the echocardiogram without epicardial spasm ≥ 90%.6

Indices obtained with continuous thermodilution

After the administration of unfractionated heparin (70 IU/kg), a pressure-temperature sensor guidewire Pressure Wire X (Abbott, United States) was inserted and pressures at the catheter distal border were equalized. The guidewire was advanced until it reached the left anterior descending coronary artery distal segment.

Resting full-cycle ratio was registered to confirm the lack of hemodynamically significant epicardial stenoses (RFR > 0.89).

Afterwards, a specific Rayflow (Hexacath, France) microcatheter for intracoronary infusion was placed in the left anterior descending coronary artery proximal segment. After confirmation that the guidewire sensor was, at least, 3 cm distal to the tip of the microcatheter, the intracoronary infusion of a physiological saline solution at room temperature and at a dose of 20 mL/min was started using an injector pump to induce hyperemia.

Pressure-temperatures curves were registered using Coroventis software (Abbott, United States). When the distal temperature drop was stabilized, the sensor was withdrawn up to the tip of the microcatheter to determine the infusion temperature.

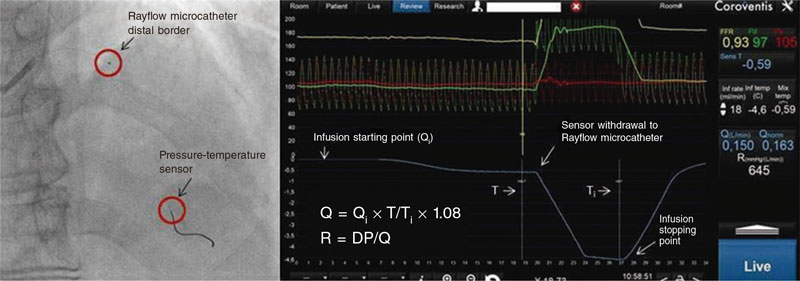

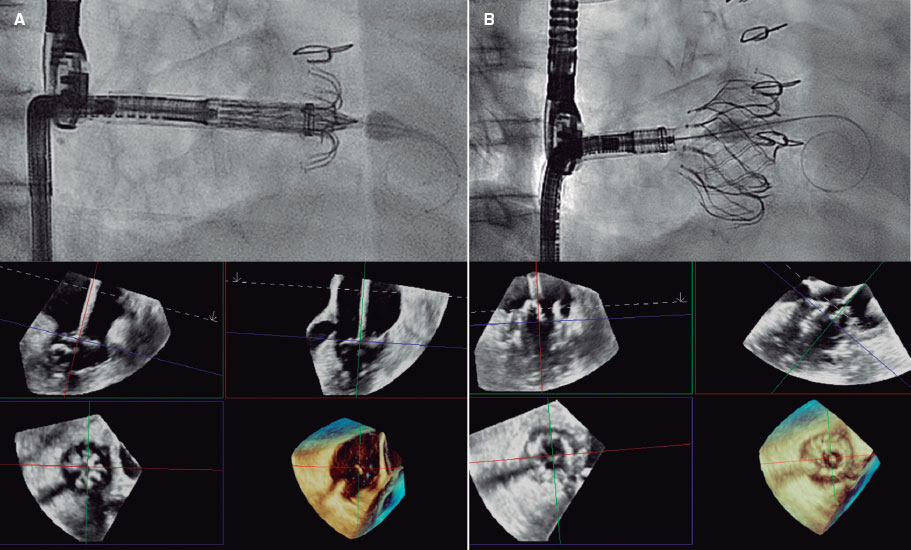

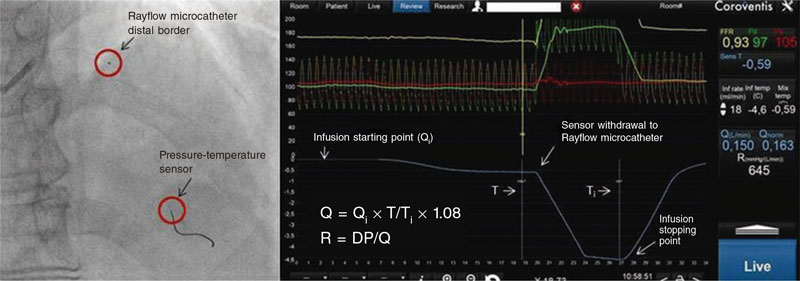

Afterwards, the injection of the physiological saline solution stopped, and Q (L/min) and R (Wood units) values were obtained automatically (figure 1).

Figure 1. Measurements obtained by continuous thermodilution: DP, distal pressure; Q, absolute coronary blood flow; Qi, infusion flow (mL/min); R, microvascular resistance; T, distal temperature; Ti, infusion temperature.

Indices obtained with bolus thermodilution of a physiological saline solution

After completion of the continuous thermodilution study, and once the Rayflow microcatheter was removed, the pressure-temperature guidewire was repositioned in its previous location, and thermodilution curves were registered using the Coroventis software after the vigorous manual injection of 3 intracoronary boluses of 3 mL of a physiological saline solution. Measurements were taken at rest and after inducing hyperemia with a peripheral intravenous bolus of regadenoson (400 µg) resulting in the calculation of CFR and IMR.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. The categorical ones were expressed as absolute value or percentage. ROC (Receiver operating characteristic) curves were used to estimate the optimal cut-off values for the continuous variables Q and R. The cut-off values established as pathological for CFR < 2 and IMR ≥ 25 were used as the reference framework. Once dichotomized, the variables Q and R were compared to the CFR and IMR values using chi-square tests. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the different quantitative variables. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v 20 statistical software package (IBM, United States).P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study patients

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 60 patients included in the study. Women (55%) were predominant. Also, there was a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. Most showed typical angina-like clinical signs (76%) and had tested positive to an ischemia test performed before the coronary angiography (60%).

Table 1. Clinical and angiographic characteristics (N = 60)

| Age (years) | 63 ± 10 |

| Women | 33 (55%) |

| Hypertension | 39 (65%) |

| Diabetes | 21 (35%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 35 (58%) |

| Smoking (current or past) | 28 (47%) |

| Previous percutaneous revascularization | 4 (7%) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 3 (5%) |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 4 (7%) |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 63 ± 8 |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Exertional angina | 19 (32%) |

| Resting angina | 13 (22%) |

| Mixed angina | 14 (23%) |

| Other | 14 (24%) |

| Ischemia test | |

| Ergometry | 19 (32%) |

| Isotopic scintigraphy | 18 (30%) |

| Dobutamine stress echocardiography | 3 (5%) |

| None | 20 (33%) |

| Coronary angiography | |

| Atheromatous disease | 22 (37%) |

| Slow flow | 13 (22%) |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|

The baseline coronary angiography confirmed that 37% of the patients showed parietal irregularities consistent with atheromatous disease, and 22% had slow coronary flow. The FFR and RFR values were normal in all the cases studied.

Coronary vasoreactivity

As shown on table 2, 60% of the cases (36/60) had a positive response to acetylcholine in the vasoreactivity test. A total of 32% of the cases (19/60) showed severe epicardial vasoconstriction, and 23% (14/60) met the criteria for microvascular spasm. In 3 patients (5%), microvascular spasm was observed concomitantly with the medium dose (20 µg), and epicardial spasm with the high dose (100 µg), which added to the impaired indices of microvascular function was consistent with a mixed endotype.

| Pathological vasoreactivity testing | 36 (60%) |

| Epicardial vasospasm | 19 (32%) |

| Microvascular vasospasm | 14 (23%) |

| Combined vasospasm | 3 (5%) |

| Structural microvascular dysfunction (IMR ≥ 25) | 20 (33%) |

| Isolated | 5 (8%) |

| Associated with epicardial spasm | 8 (13%) |

| Associated with microvascular spasm | 4 (7%) |

| Associated with combined spasm | 3 (5%) |

| CFR < 2 | 11 (18%) |

| CFR < 2.5 | 17 (28%) |

| RFR | 0.93 [0.91-0.94] |

| FFR | 0.90 [0.87-0.93] |

| Q (mL/min) | 170 ([138-219] |

| R (WU) | 496 [381-654] |

| CFR | 3.0 [2.3-4.2] |

| IMR | 20 [12-28] |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range]. |

|

Indices of microvascular function

Both studies—bolus thermodilution and continuous infusion thermodilution—were performed uneventfully in all of the patients. Table 2 shows the values of the measurements of microvascular function obtained with both techniques.

In the continuous infusion study, a median of absolute flow in the left anterior descending coronary artery of 170 mL/min [138-219 mL/min] was described while the median of microvascular resistance was 496 WU [381-654 WU].

A total of 18% of the patients (11/60) had a reduced CFR (CFR < 2) while 33% (20/60) showed elevated resistances (IMR ≥ 25).

The group of patients with microvascular dysfunction due to low CFR with normal IMR (7/60, 12%) with respect to cases with microvascular dysfunction due to high IMR with normal CFR (16/60, 27%) had a clinical profile with a lower mean age (61 ± 11 vs 66 ± 8), and a higher predominance of women (86% vs 58%) although this tendency was not statistically significant.

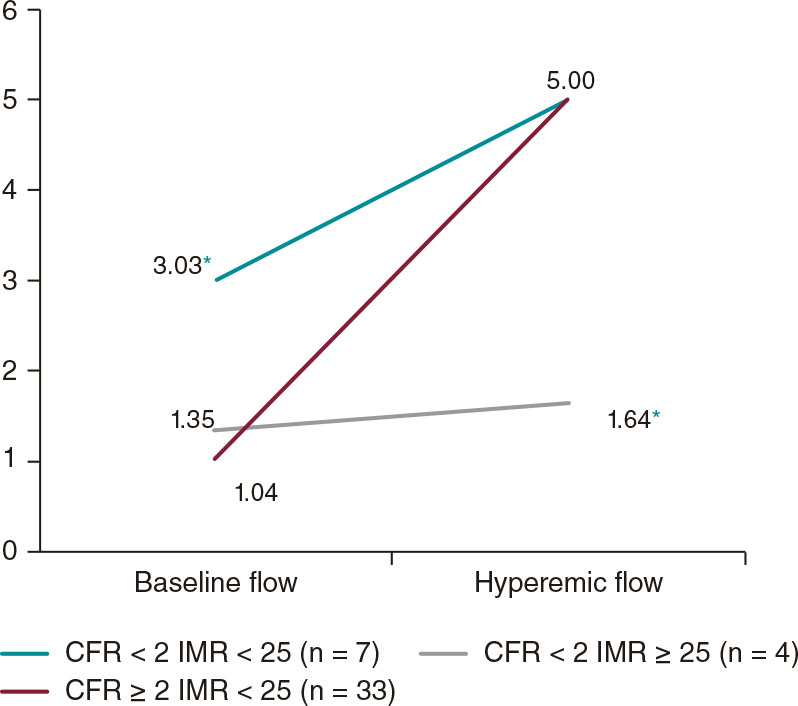

Table 3 shows the mean transit times (MTT) of bolus thermodilution tests. The cases with low CFR showed significantly shorter baseline MTT (0.48 ± 0.45 vs 1.13 ± 0.70), especially the subgroup of patients with low CFR and high Q (0.31 ± 0.15 vs 0.77 ± 0.68).

Table 3. Mean transit times obtained by bolus thermodilution

| Overall (N = 60) |

CFR < 2 (N = 11) |

CFR < 2 Q > 170 (N = 7) |

CFR < 2 Q < 170 (N = 4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline MTT | 1.13 ± 0.70 | 0.48 ± 0.45* | 0.31 ± 0.15* | 0.77 ± 0.68 |

| Hyperemic MTT | 0.36 ± 0.25 | 0.35 ± 0.28 | 0.25 ± 0.14 | 0.51 ± 0.41 |

|

Values (in seconds) are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. |

||||

Figure 2 shows data of coronary flow estimated by MTT measurement divided into 3 groups based on CFR and IMR results. We should mention that patients with low CFR without elevated resistances had significantly high resting flows and hyperemic flows without significant differences compared to the rest while in patients with low CFR and elevated resistances, the opposite phenomenon was described.

Figure 2. Baseline and hyperemic mean flow estimated based on the MTT (1/MTT) and grouped based on the CFR and IMR results. Values are expressed as s–1. CFR, coronary flow reserve; IMR, index of microvascular resistance; MTT, mean transit time.

* P < .05.

Endotypes

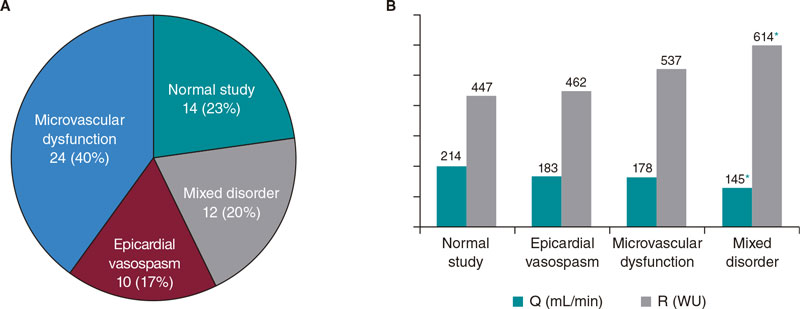

Figure 3A shows the percentages of endotypes based on the result of the acetylcholine test and the measurements of CFR and IMR. The most common pattern was microvascular dysfunction (24/60, 40%) followed by the normal study (14/60, 23%). In 20% of the patients (12/60), microvascular dysfunction overlapped with epicardial vasospasm while in 17% of the patients (10/60) isolated epicardial vasospasms were seen.

Figure 3. A: endotype-based classification. Values are expressed as absolute number and percentage.B: mean values of absolute flow and microvascular resistance grouped by endotypes. Q, absolute coronary blood flow; R, microvascular resistance.

* P < .05 with respect to normal study.

Table 4 shows how the mechanisms of vasomotor and microvascular dysfunction overlap in many cases.

Table 4.Results of the acetylcholine test and bolus thermodilution study (N = 60)

| Epicardial spasm | Microvascular spasm | IMR ≥ 25 | CFR < 2 | Endotype | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | − | − | − | Normal | 14 (23.3%) |

| + | − | − | − | Epicardial vasospasm | 10 (16.7%) |

| − | + | − | − | Microvascular dysfunction | 9 (15.0%) |

| − | − | + | − | Microvascular dysfunction | 5 (8.3%) |

| − | − | − | + | Microvascular dysfunction | 5 (8.3%) |

| − | + | + | − | Microvascular dysfunction | 3 (5.0%) |

| − | + | − | + | Microvascular dysfunction | 1 (1.6%) |

| − | + | + | + | Microvascular dysfunction | 1 (1.6%) |

| + | − | + | − | Mixed disorder | 6 (10.0%) |

| + | + | + | − | Mixed disorder | 2 (3.3%) |

| + | − | + | + | Mixed disorder | 2 (3.3%) |

| + | − | − | + | Mixed disorder | 1 (1.6%) |

| + | + | + | + | Mixed disorder | 1 (1.6%) |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%) |

|||||

The association between epicardial vasospasm and structural microvascular dysfunction (IMR ≥ 25) was the most prevalent combination in cases of mixed disorder (11/12). In turn, this endotype, in continuous thermodilution measurements, showed significant differences compared to the normal pattern, with reduced absolute flow values and elevated resistances (figure 3B) indicative of more serious structural and functional damage.

Concordance among the different indices of microvascular function

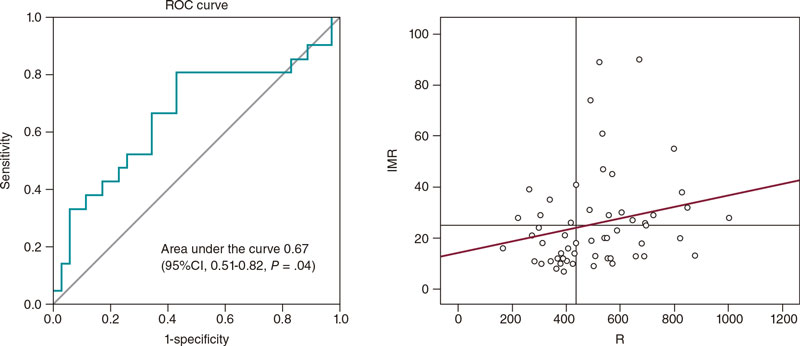

The ROC curve analysis of absolute coronary blood flow (Q) with respect to CFR < 2 determined an optimal cut-off value of 170 mL/min (a 64% sensitivity, and a 52% specificity) with an area underthe curve of 0.50 (95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.33-0.66;P = .97), therefore showing no diagnostic utility.

Given the recent proposal to consider the cut-off value of CFR < 2.57,7 the analysis was performed using this threshold as the reference. In addition, no significant concordance was seen (area under the curve of 0.45 [95%CI, 0.30-0.61;P = .56]).

Regarding R with respect to IMR, an area under the curve of 0.67 (95%CI, 0.51-0.82;P = .04) was obtained, which was indicative of a weak yet significant diagnostic concordance (figure 4). The estimated optimal cut-off value was 435 WU, which was consistent with an 81% sensitivity and a 57% specificity. A total of 66% of cases with IMR ≥ 25 were categorized correctly using this index.

Figure 4. Analysis of the R cut-off value > 435 WU to predict IMR ≥ 25, and scatter plot showing the correlation between IMR and R. IMR, index of microvascular resistance; R, microvascular resistance.

The absence of an association between Q and CFR was confirmed in correlation tests (Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient= -0.02; 95%CI, -0.24-0.25;P = .99). However, a weak yet significant correlation was seen between Q and hyperemic MTT (Spearman’s rho= -0.28; 95%CI, -0.01-0.51;P = .04), and between R and IMR (Spearman’s rho= 0.28; 95%CI, 0.04-0.51;P = .03).

Complications

While the vasoreactivity test was being performed, 3 cases of transient bradycardia (5%) without clinical repercussions and 2 episodes of atrial fibrillation (4%) were reported, 1 of them self-limited while the other required sedation and electrical cardioversion. After the administration of regadenoson, most patients experienced some degree of discomfort, which was well-tolerated and reversed with the administration of 100 mg of intravenous theophylline. No other complications or adverse effects were reported.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that a high percentage of patients with symptoms or signs of INOCA show microvascular dysfunction or vasospasm in invasive functional testing, and that it is feasible and safe to perform (figure 5).

Figure 5. Study design, endotype-based classification, and analysis using the ROC curve. AUC, area under the curve; CFR, coronary flow reserve; IMR, index of microvascular resistance; INOCA, ischemia with nonobstructive coronary artery disease; Q, absolute coronary blood flow; R, microvascular resistance.

* P < .05.

The percentage of patients with microcirculation or vasomotility alterations found in our study (77%) is consistent with former studies of patients with angina without obstructive coronary artery disease (64% to 89%8-11).

Vasoreactivity test

Some groups systematically use a dose of 200 µg of intracoronary acetylcholine to perform the vasoreactivity test; in our study, the high dose was established at 100 µg according to the COVADIS group, the CorMicA protocol, and the technical document of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology, which highlights its high sensitivity and specificity rates (90% and 99%, respectively).12 As a matter of fact, the high prevalence of positive results seen in our study in the acetylcholine test (60%) is similar to that reported in other series (57% to 71%13-15). In a recent study of 110 patients, Feenstra et al.11 revealed that 62% of the patients had a pathological acetylcholine test that confirmed the presence of epicardial vasospasm and microvascular spasm (36% and 26%, respectively).

In our study, the complications associated with the vasoreactivity test in our study are not very many: 2 cases of atrial fibrillation (4%), which is consistent with the incidence rate reported by the CorMIcA trial (5%).9

Prevalence of endotypes

The most common endotype in our patients was isolated microvascular dysfunction (40%), but not as much as in the CorMicA trial (52%). These differences could be explained by the discrepancy seen in the percentage of completely normal angiographies (22% in the CorMicA vs 63% in our study) due to the possible association between non-obstructive atheromatous disease and microvascular dysfunction.16,17

The prevalence of the remaining endotypes is similar to that reported in the CorMicA trial: isolated epicardial vasospasm (17% vs 17%), and mixed disorder (20% vs 21%). A recent meta-analysis that included 14 427 patients with INOCA also shows similar percentages.18

Indices of microvascular function obtained through bolus thermodilution

The analysis of the MTT obtained with this technique (figure 2), a parameter that correlates inversely with the direct measurement of coronary flow,19 reveals an interesting finding that is consistent with the data published by Nardone et al.20: patients with low CFR have 2 differentiated phenotypes based on the IMR. On the one hand, cases with reduced CFR and elevated resistances have normal baseline flow and low hyperemic flow, which would be indicative of an insufficient vasodilation response. However, in patients with normal resistances, a reduced CFR would be indicative of an abnormally elevated resting flow with hyperemic flow in the normal range. This phenomenon can also be observed in the analysis of patients with high Q (table 3) in whom a reduced CFR can be attributed to elevated baseline flow instead of an insufficient hyperemic response.

Therefore, this subgroup probably shows inefficient or dysregulated baseline myocardial flows. This characteristic, of indeterminate cause, could have important therapeutic implications like a lack of response to vasodilator drugs.

Indices of microvascular function obtained by continuous thermodilution

The continuous thermodilution technique has evolved to the point of quantifying Q and R with a microcatheter and specific software in a simple and precise fashion. The main advantages of this method are its independence from an operator, reproducibility, and induction of hyperemia with a physiological saline solution without the need for pharmacological agents.21-24 However, its main limitation is the lack of normal reference values.

In our study, the lack of a correlation between Q and CFR could be justified by the variations described of baseline myocardial flow. Estimating the CFR requires estimating the baseline coronary flow while Q is a measurement that is representative of hyperemic flow.

The weak concordance seen in this study between Q and hyperemic MTT and between R and IMR shows how difficult it is to establish valid cut-off values for patient comparison with these indices.

With an optimal cut-off value of R in our study of 435 WU (an 81% sensitivity, and a 57% specificity), a total of 66% of cases with IMR ≥ 25 were properly categorized with this index. This value is somewhat lower compared to the one shown by Rivero et al.,25 who analyzed 120 patients and found that an R > 500 WU properly categorized 80% of the cases with IMR ≥ 25.Konst et al.26 studied 84 patients with INOCA using both thermodilution techniques only to find no correlation between the Q-R combo and IMR.

The differences seen may be explained by the fact that the quantitative variability of Q and R values among individuals mostly depends on myocardial mass. However, in positron emission tomography studies, considerable ranges were seen even after adjusting for flow and resistance values for myocardial mass. Therefore, it has been speculated that the most plausible hypothesis is the natural variation of hyperemic myocardial perfusion among individuals.27

Therefore, indices like CFR estimated by continuous thermodilution and microvascular resistance reserve are currently in the pipeline. They correlate the absolute values of flow and resistance seen during hyperemia with those obtained at rest. Nonetheless,these new parameters will still need validation in futurestudies.28,29

Limitations

The data presented here should be interpreted while understanding that this is an observational, single-center study with a small sample size. Therefore, results may be biased by confounding factors associated with a study of this nature.

The left anterior anterior descending coronary artery was considered as the pre-specified target vessel. However, in the routine clinical practice, it may be appropriate to assess other arteries in the presence of negative tests and high clinical suspicion.1

The optimal sequence in invasive functional studies has not been established yet.1 In our case, we chose to perform the acetylcholine test first to minimize the instrumentation of the artery and avoid further guidewire-induced vasoreactivity. However, the spasm and symptoms seen during the provocation test, although transient, could interfere with subsequent measurements of microvascular function. The possibility of determining CFR by continuous thermodilution was established at the beginning of our study, and it was assumed that a comparison of the CFRs obtained with both techniques would have been more appropriate.

In most bolus thermodilution studies, intravenous adenosine is used to induce hyperemia. However, we chose regadenoson because it is easy to use, following our previous experience, and because evidence says it is equivalent to adenosine.30,31

Finally, we should not overlook that this is an invasive study so potential risks associated with the examination should be weighed in. To this date, however, conducting this study has not impacted prognosis.

CONCLUSIONS

The invasive study of coronary vasoreactivity and microcirculation is feasible and safe. These studies allow us to easily recognize different endotypes of patients with INOCA and help us optimize their treatment.

The analysis of CFR, IMR, and Q combined can unmask a subtype of microvascular dysfunction characterized by an abnormally high baseline coronary flow.

The new indices obtained by continuous thermodilution show low concordance with respect to the reference indices. Therefore, future studies will be required to determine the utility of this technique.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed substantially to the study idea, design, and data mining process. In addition, all approved the manuscript final version for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- The invasive diagnosis of microvascular dysfunction and coronary vasospasm have proven useful to improve the quality of life of patients without obstructive coronary artery disease on the coronary angiography.

- Indices of microvascular dysfunction obtained by continuous thermodilution offer potential advantages since are they are independent from the operator, reproducible, and do not require pharmacologically induced hyperemia.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Invasive coronary functional diagnosis is feasible and safe and highlights the high prevalence of microcirculation and vasomotility alterations in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease.

- The combined analysis of the different indices may be useful to characterize cases with decreased CFR.

- Future studies are needed to establish the utility of microvascular function measurements obtained by continuous thermodilution.

REFERENCES

1. Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG, et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3504-3520.

2. Camici PG, Crea F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:830-840.

3. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407-477.

4. Ford TJ, Ong P, Sechtem U, et al. COVADIS Study Group. Assessment of Vascular Dysfunction in Patients Without Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Why, How, and When. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1847-1864.

5. Xaplanteris P, Fournier S, Keulards DCJ, et al. Catheter-Based Measurements of Absolute Coronary Blood Flow and Microvascular Resistance: Feasibility, Safety, and Reproducibility in Humans. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e006194.

6. Beltrame JF, Crea F, Kaski JC, et al., On Behalf of the Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS). International standardization of diagnostic criteria for vasospastic angina. Eur Heart J. 2015;38:

2565-2568.

7. Demir OM, Boerhout CKM, de Waard GA, et al. Comparison of Doppler Flow Velocity and Thermodilution Derived Indexes of Coronary Physiology. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:1060-1070.

8. Suda A, Takahashi J, Hao K, et al. Coronary functional abnormalities in patients with angina and nonobstructive coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2350-2360.

9. Ford TJ, Stanley B, Good R, et al. Stratified medical therapy using invasive coronary function testing in angina: the CorMicAtrial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2841-2855.

10. Sara JD, Widmer RJ, Matsuzawa Y, Lennon RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prevalence of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Among Patients With Chest Pain and Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1445-1453.

11. Feenstra RGT, Boerhout CKM, Woudstra J, et al. Presence of Coronary Endothelial Dysfunction, Coronary Vasospasm, and Adenosine-Mediated Vasodilatory Disorders in Patients With Ischemia and Non obstructive Coronary Arteries. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:e012017.

12. Gutiérrez E, Gómez-Lara J, Escaned J, et al. Valoración de la función endotelial y provocación de vasoespasmo coronario mediante infusión intracoronaria de acetilcolina. Documento técnico de la ACI-SEC. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:286-296.

13. Aziz A, Hansen HS, Sechtem U, Prescott E, Ong P. Sex-Related Differences in Vasomotor Function in Patients With Angina and Unobstructed Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2349-2358.

14. Seitz A, Gardezy J, Pirozzolo G, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up in Patients With Stable Angina and Unobstructed Coronary Arteries Undergoing Intracoronary Acetylcholine Testing. J Am Coll Cardiol Interv. 2020;13:1865-1876.

15. Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Borgulya G, et al. Clinical usefulness, angiographic characteristics, and safety evaluation of intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing among 921 consecutive white patients with unobstructed coronary arteries. Circulation. 2014;129:1723-1730.

16. Melikian N, Vercauteren S, Fearon WF, et al. Quantitative assessment of coronary microvascular function in patients with and without epicardial atherosclerosis. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:939-945.

17. Sharaf B, Wood T, Shaw L, et al. Adverse outcomes among women presenting with signs and symptoms of ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: findings from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) angiographic corelaboratory. Am Heart J. 2013;166:134-141.

18. Mileva N, Nagumo S, Mizukami T, et al. Prevalence of Coronary Microvascular Disease and Coronary Vasospasm in Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023207.

19. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Smith L, et al. Coronary thermodilution to assess flow reserve: experimental validation. Circulation. 2001;104:2003-2006.

20. Nardone M, McCarthy M, Ardern CI, et al. Concurrently Low Coronary Flow Reserve and Low Index of Microvascular Resistance Are Associated With Elevated Resting Coronary Flow in Patients With Chest Pain and Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:e011323.

21. Van’t Veer M, Adjedj J, Wijnbergen I, et al. Novel monorail infusion catheter for volumetric coronary blood flow measurement in humans: invitro validation. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:701-707.

22. Rivero F, Bastante T, Cuesta J, García-Guimaraes M, Maruri-Sánchez R, Alfonso F. Volumetric Quantification of Coronary Flow by Using a Monorail Infusion Catheter: Initial Experience. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:1082-1084.

23. Everaars H, de Waard GA, Schumacher SP, et al. Continuous thermodilution to assess absolute flow and microvascular resistance: validation in humans using [15O] H2O positron emission tomography. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2350-2359.

24. Keulards DCJ, Van’t Veer M, Zelis JM, et al. Safety of absolute coronary flow and microvascular resistance measurements by thermodilution. EuroIntervention. 2021;17:229-232.

25. Rivero F, Gutiérrez-Barrios A, Gomez-Lara J, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction assessed by continuous intracoronary thermodilution: A comparative study with index of microvascular resistance. Int J Cardiol. 2021;333:1-7.

26. Konst RE, Elias-Smale SE, Pellegrini D, et al. Absolute Coronary Blood Flow Measured by Continuous Thermodilution in Patients With Ischemia and Nonobstructive Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:728-741.

27. Fournier S, Keulards DCJ, van’t Veer M, et al. Normal values of thermodilution-derived absolute coronary blood flow and microvascular resistance in humans. EuroIntervention. 2021;17:e309-e316.

28. Gutiérrez-Barrios A, Izaga-Torralba E, Rivero Crespo F, et al. Continuous Thermodilution Method to Assess Coronary Flow Reserve. Am J Cardiol. 2021;141:31-37.

29. De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Gallinoro E, et al. Microvascular Resistance Reserve for Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Function: JACC Technology Corner. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1541-1549.

30. Federico P, Martínez L, Castelló T, Pomar F, Peris E. Regadenoson intravenoso frente a adenosina intracoronaria para la medida de la reserva fraccional de flujo. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:77-82.

31. Gill GS, Gadre A, Kanmanthareddy A. Comparative efficacy and safety of adenosine and regadenoson for assessment of fractional flow reserve: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Cardiol. 2022;14:

319-328.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: pau@comv.es (P. Federico Zaragoza).

ABSTRACT

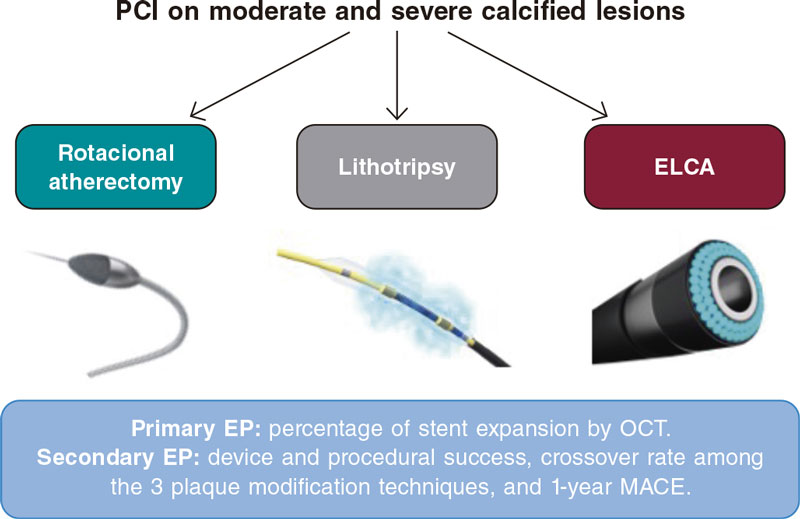

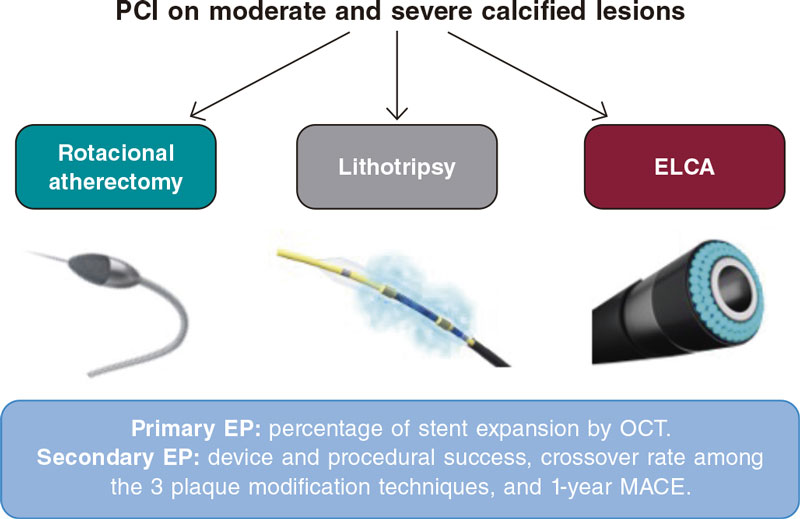

Introduction and objectives: Coronary calcification is one of the leading factors that affect negatively the safety and effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention. Several calcium modification techniques exist. However, there is a lack of randomized evidence on the therapy of choice in this scenario.

Methods: The ROLLERCOASTR is a prospective, multicenter, randomized clinical trial designed to compare the safety and efficacy profile of 3 plaque modification techniques in the moderate-to-severe coronary calcification setting: rotational atherectomy (RA), excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA), and intravascular lithotripsy (IVL). The study primary endpoint is stent expansion evaluated by optical coherence tomography. An intention-to-treat analysis will be conducted with an alpha coefficient of 0.05 between the reference group (RA) and the remaining 2 groups (ELCA and IVL). An analysis of the study primary endpoint per protocol will be conducted for consistency purposes. If the non-inferiority hypothesis is confirmed, a superiority 2-sided analysis will be conducted. Both the clinical events committee and the independent core laboratory will be blinded to the treatment arm. Assuming an α error of 0.05, an β error of 0.2 (80% power), a margin of irrelevance (ε) of 7, and losses of 10% due to measurement difficulty or impossibility to complete the intervention, we estimate a sample size of 56 cases per group. The study secondary endpoints are device success, procedural success, crossover rate among the different techniques used, and the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusions: The ROLLERCOASTR trial will evaluate and compare the safety and effectiveness of 3 plaque modification techniques: RA, ELCA, and IVL in patients with calcified coronary stenosis. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov with identifier NCT04181268.

Keywords: Percutaneous coronary intervention. Calcified plaques. Laser. Lithotripsy. Rotational atherectomy. Optical coherence tomography.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La calcificación coronaria es uno de los principales factores que inciden negativamente en la seguridad y la eficacia del intervencionismo coronario percutáneo. Existen varias técnicas de modificación del calcio, pero falta evidencia de estudios aleatorizados sobre la terapia de elección en este escenario.